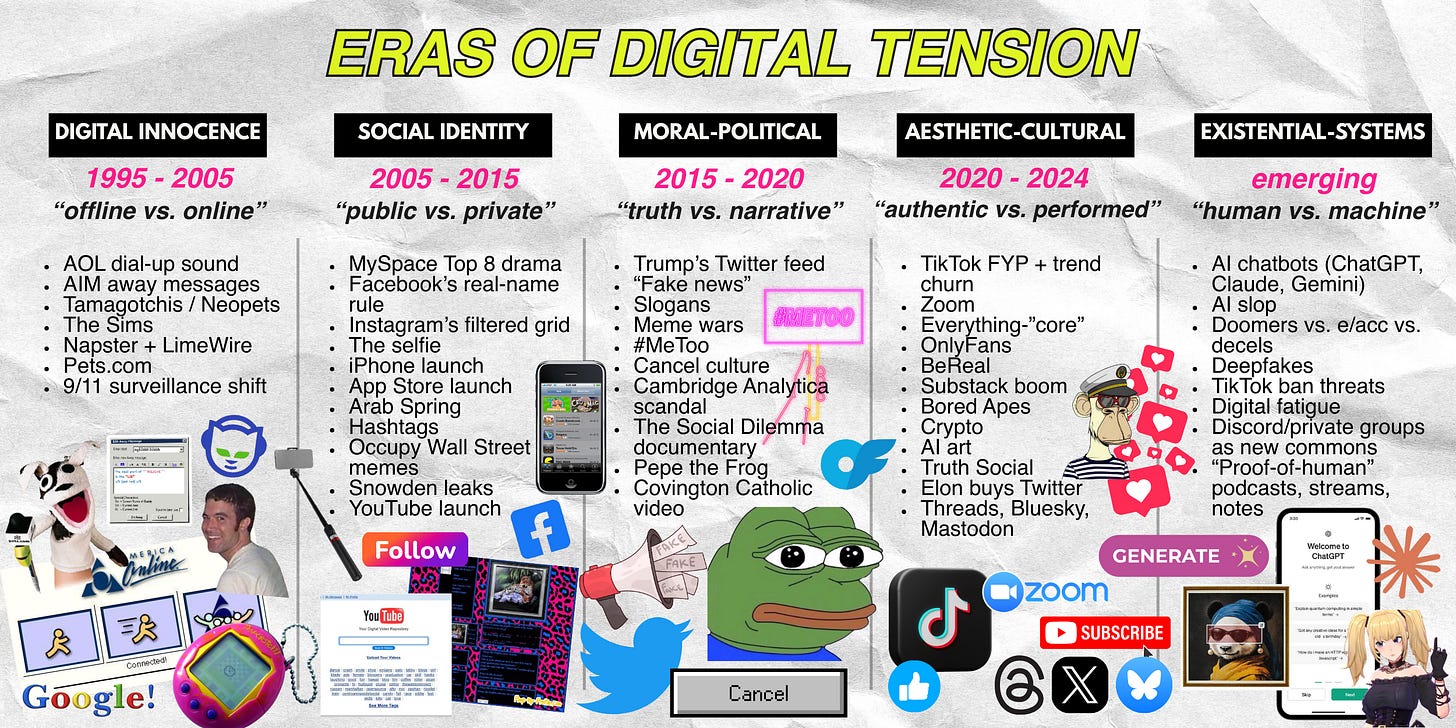

From Tamagotchis and Dial-Up to the Age of AI

a timeline of the digital tensions that rewired culture

“You’ve got mail!”

When I was growing up, “going online” was an event. You sat at a family computer, dialed through the metallic shriek of a modem, and entered a world that felt separate from the one outside your door. Maybe you fed your Tamagotchi, updated your MySpace profile song, or waited twenty minutes for a Napster download to finish. It was slow, awkward, and somehow felt innocent.

But that innocence didn’t last. Over the past three decades, the internet has moved from playful experiment to political battlefield, from a space of performance to one of collapse and reinvention. Each era carried its own cultural tension—between real and virtual, public and private, truth and narrative, authenticity and performance—and now, human and machine.

This piece is an attempt to trace those shifts. Not just the technologies themselves, but the cultural inflection points—the memes, scandals, apps, and movements—that revealed what was at stake. What follows is a timeline of how the digital world grew up, and how we grew up with it. It isn’t only nostalgia, but a way of making sense of why online life feels the way it does today—fractured, accelerated, and often overwhelming. By tracing the tensions of each era, you’ll see how each stage set up the next, and why the platforms, debates, and anxieties we live with now didn’t appear out of nowhere. Think of it less as a history lesson and more as a map that shows how culture was rewired in real time.

quick note on the timeline—

You might notice the eras get shorter as the timeline moves forward—ten years, then five, then barely two or three. That’s not an accident. Each cycle of the internet has accelerated on the back of the last one. The time between “new toy” and “existential reckoning” keeps collapsing. Scholars sometimes call this the acceleration of history—what once unfolded over a decade now combusts in months. The dot-com bubble took years to inflate; TikTok took just a summer. The closer we get to the present, the faster the ground shifts.

DIGITAL INNOCENCE (1995–2005)

the tension: real vs. virtual

THERE WAS A TIME WHEN being “online” was still optional. The internet wasn’t life yet; it was a side-channel—something you logged into, not something that followed you into every room. The dial-up modem announced that you were entering a separate world. That boundary was important. Real life and virtual life still felt distinct.

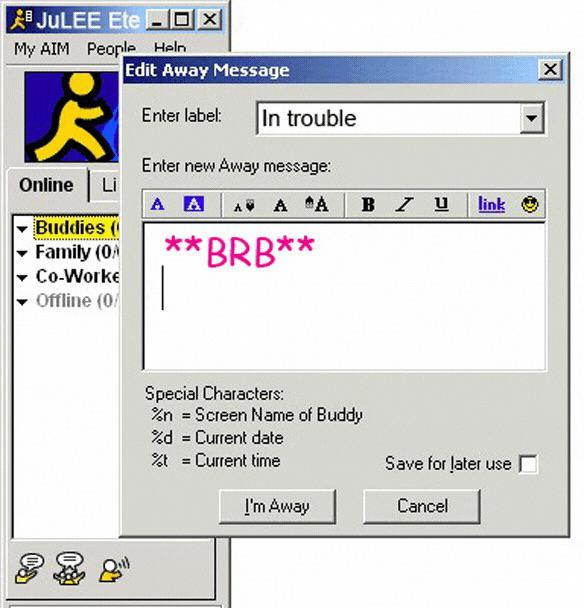

If you were born after 2000, here’s what logging on used to sound like for us old folk:

Logging in was an event. You claimed the family computer, hoped no one picked up the landline, and waited for AOL to connect. Once online, you curated yourself through little gestures: AIM away messages quoting song lyrics or cryptic lines that hinted at your mood; MSN Messenger usernames dressed up with alternating caps and symbols; GeoCities pages dripping with glitter GIFs. These were the first status updates—the first attempts at making your interior life visible in text and code.

This was the age of Tamagotchis, Neopets, and The Sims—digital pets and digital houses that ran in parallel to your own. (Shout out to the kids who kept keychains absolutely filled with beeping NeoPets!) Playful prototypes for digital responsibility, identity, and addiction—experiments in what it meant to care for, create, and control a parallel self.

On Geocities and early MySpace, users became accidental coders, copying and pasting HTML to turn their pages into flashing shrines of personality. Glitter text, autoplay music, tiled backgrounds—it was the digital version of spray-painting your bedroom walls. MySpace even gave rise to the profile customization site “pimp my profile,” a nod to MTV’s Pimp My Ride.

Napster cracked open another layer: music as free, infinite, uncontrollable. Suddenly, what you consumed wasn’t what you bought at Sam Goody but what you could download at 2 a.m. on a dial-up connection. Songs that once required $18 for a CD now lived in shared folders passed between strangers. “Information wants to be free” wasn’t just an ethos, it was a loophole. The cultural tension emerged quickly: freedom vs. ownership, sharing vs. stealing. Capitalism had never faced a world where copy-paste could erase scarcity.

Silicon Valley was in full speculative mania. Startups like Pets.com, Webvan, and eToys went public with little more than business plans, yet stock prices soared on hype. Super Bowl ads sniffed opportunity: the Pets.com sock puppet wasn’t just cute, it was a billboard for how fast brands would rush to colonize the new frontier. (The brand might not have made it, but their commercials will live in my heart forever—see YouTube vid below). Between 1995 and early 2000, the Nasdaq climbed nearly 400%, fueled less by profits than by the belief that “anything with a dot-com” was the future.

The collapse came fast. As investors realized many of these companies had no path to profitability—burning cash on ads, free shipping, or unsustainable growth—confidence vanished. By March 2000, the Nasdaq began its freefall, losing almost 80% of its value over two years. Trillions in paper wealth disappeared, and thousands of startups folded. For many, it felt like the internet itself had been exposed as a failed experiment.

In hindsight, it was only a rehearsal. The excess collapsed, but the scaffolding remained: broadband lines, early e-commerce infrastructure, search engines like Google. What looked like ruin at the time was actually the foundation for the next wave.

Innocence ended in another way, too. After 9/11, digital life became bound up with fear and surveillance. Media panic about “online predators” blurred into larger anxieties about strangers and hidden threats. The Patriot Act expanded government surveillance, and the internet shifted from a quirky playground to a tool for monitoring and control.

What began as play was suddenly reframed: the same technology that let you download a song at midnight could also be used to track, watch, or deceive.

CULTURAL MARKERS OF THE ERA—

Dial-up modem sound: the shriek that signaled you were crossing into another world

AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) away messages: proto-status updates, mood + song lyrics as identity

GeoCities and Angelfire websites: chaotic, glittering, homemade web pages

Tamagotchis, Neopets, The Sims: training grounds for digital care, identity, and addiction

Napster & Limewire: “free” music culture, piracy as norm

Pets.com sock puppet ad (Super Bowl 2000): dot-com hype crystallized

9/11 + Patriot Act: internet shifts from playful space to surveillance tool

SOCIAL IDENTITY TENSION (2005–2015)

the tension: public vs. private

IF THE FIRST DECADE OF the internet was play, the second was performance. The wall between real and virtual began to thin, and the online self became inseparable from the offline one. MySpace profiles, then Facebook, then Instagram each raised the stakes of self-presentation. Who you were online was no longer parallel to your life—it was your life, projected, filtered, and archived.

Each platform marked a step forward in turning identity into performance. MySpace let users build glittering, chaotic, customized pages—your taste in music, movies, and friends became your brand. Facebook stripped away the glitter and demanded real names, real networks, and real photos. It normalized the “social graph,” the idea that your offline relationships should be mapped, quantified, and visible to others. Then Instagram took it further by perfecting the feed: a grid of filtered photos, cropped and staged to broadcast a polished self. What began as messy experimentation hardened into something closer to a public résumé.

When YouTube launched in 2005 with its slogan “Broadcast Yourself,” it lowered the barrier to fame to zero. Viral videos proved that ordinary people could reach millions without record labels or television networks. Suddenly anyone with a webcam and an idea could be a broadcaster. Old Spice’s 2010 ‘The Man Your Man Could Smell Like’ response videos turned a commercial into a two-way show—proof that marketing had become content, and audiences expected to talk back. These were the seeds of influencer culture, long before the word “influencer” existed.

The iPhone’s launch in 2007 sealed this shift. We no longer logged on; we were always online. The phone in your pocket became an extension of identity. Every moment was a potential post. The App Store, launched a year later, multiplied that effect. Suddenly there wasn’t just one portal, but thousands of apps that let you filter, post, track, and perform your life in real time. Instagram (2010) and Snapchat (2011) rode this wave, turning the camera from a tool for memory into a stage for the self.

In 2013, the Oxford English Dictionary declared “selfie” the Word of the Year, solidifying the cultural shift. What had started as awkward mirror shots became a default mode of expression. The act of documenting yourself wasn’t just normalized—it was celebrated. The self itself had become content.

The App Store also reshaped the economy of attention. Free apps weren’t really free; they were funded by ads, microtransactions, and endless nudges to keep you engaged. Behavior itself became a business model. Swiping, liking, posting—actions that once felt casual—were now monetized at scale. Apple’s ‘There’s an app for that’ didn’t just sell phones; it taught brands to live inside your pocket—loyalty programs, push alerts, and micro-ads as daily ritual. This was the beginning of the trade-off: convenience in exchange for being watched.

This was also the decade when platforms hardwired psychology into design. Likes, favorites, retweets, and follows created an endless slot machine of validation. Intermittent rewards—a heart here, a follow there—kept users hooked. And “followers” collapsed hierarchies: suddenly politicians, celebrities, and your neighbor were all in the same game of accumulation. Obama’s 2008 campaign using Twitter or celebrities racing to hit a million followers showed how influence was quantified in public for the first time. Everyone had an audience now—and everyone was expected to perform for it.

Even so, this era carried a strange optimism about connectivity. Twitter and Facebook were celebrated as forces for democracy. During the Arab Spring—a wave of pro-democracy uprisings that spread across the Middle East and North Africa between 2010 and 2012—activists in Tunisia, Egypt, and beyond used social platforms to organize protests and broadcast events to the world in real time. Western media framed it as proof that social media could topple dictators.

At the same time, hashtags became rallying points. From #BlackLivesMatter (first used in 2013 after the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer) to #Kony2012, hashtags compressed complex issues into viral symbols of solidarity. Even memes were treated as activism. Occupy Wall Street in 2011 spread not just as a physical protest in New York but as an online ecosystem of slogans, images, and videos. The slogan “We are the 99%” spread faster online than in Zuccotti Park, turning a movement into a viral template. The phrase fit neatly into Twitter bios, protest signs, and Tumblr posts, distilling complex critiques of inequality into a shareable identity badge.

The idea that social platforms could democratize power felt plausible. If enough people shared, posted, and tagged, it seemed like the balance of influence could shift from governments and corporations to ordinary users. But the same tools that empowered activists were quickly adopted by governments and political actors themselves. Hashtags could rally protest, but they could also spread propaganda. Networks that once looked like engines of democracy revealed themselves as engines of control.

BENEATH THE OPTIMISM, the infrastructure of surveillance capitalism began to show. Every click, like, and search became data. Google and Facebook perfected the model of trading free access for personal information. The trade-off was invisible, but not harmless.

One famous example was Target’s pregnancy-prediction algorithm. In 2012, a New York Times story revealed that the retailer had developed a system to track subtle changes in shopping habits—things like unscented lotion, cotton balls, and vitamin supplements. These signals were enough to identify women in the early stages of pregnancy. In one case, Target mailed baby coupons to a teenager, prompting her father to confront the store. Only later did he learn the algorithm had been right: his daughter was indeed pregnant.

The incident showed how corporations could know more about your private life than the people closest to you. Data wasn’t just tracking what you did—it was predicting who you were becoming.

By 2013, the curtain was pulled back. Edward Snowden’s leaks revealed the scope of the NSA’s surveillance programs, showing how entwined government and corporate tracking had become. The utopian veneer cracked and the same networks that had fueled protest also enabled unprecedented monitoring.

No matter, by the end of the decade, the cultural markers were everywhere. The word “FOMO” entered the lexicon. The selfie became a daily ritual. “Going viral” stopped being an accident and became a career path. Private life had been swallowed by public performance. This was the true social identity tension—visibility was both empowerment and exposure. To be online was to be public by default, whether you chose it or not.

CULTURAL MARKERS OF THE ERA—

MySpace Top 8: friendship politics gamified

Facebook Wall & Poke: early rituals of social mapping

Instagram filters (Valencia, X-Pro II): curated perfection as standard

“There’s an app for that” (Apple, 2009): App Store optimism

Arab Spring Twitter hashtags (2011): platforms framed as democracy engines

Occupy Wall Street memes: protest blending with internet culture

Snowden leaks (2013): optimism cracked by surveillance

Selfie stick craze: performance of the self becomes normalized

FOMO: the anxiety that defined an always-on generation

MORAL-POLITICAL TENSION (2015–2020)

the tension: truth vs. narrative

IF THE 2000s WERE ABOUT visibility and the early 2010s were about performance, the mid-to-late 2010s were about truth. The same platforms that once promised connection turned into battlegrounds for competing realities. Whose version of events would dominate—the fact-checker, the activist, the meme, or the algorithm?

The U.S. presidential election in 2016 was the crucible. On one side, Donald Trump harnessed Twitter as a direct line to voters, bypassing traditional media. On the other, Facebook was implicated in the spread of “fake news,” from conspiracy theories to fabricated headlines designed to inflame outrage. Russia’s Internet Research Agency ran troll farms that amplified division, using memes and targeted ads to pit Americans against each other.

This was the moment when memes went mainstream as political weapons. What had started on 4chan and Reddit—ironic Pepe the Frog edits, rage comics, image macros—suddenly held real-world political consequence. A frog doodle could be recast as a hate symbol by the Anti-Defamation League. Shitposting, once a subcultural joke, became a campaign strategy.

Inflection point: The 2016 U.S. election, where social platforms were no longer neutral tools but active participants in shaping outcomes.

The same year, the Brexit referendum in the UK revealed the same fault lines. Campaigns on both sides used microtargeted Facebook ads to push competing truths—promises of redirected NHS funding on one side, fears of economic collapse on the other. “Take Back Control” became a slogan optimized for virality, not accuracy.

For the first time, it became clear that political campaigns weren’t just fought on the ground or on television—they were fought in the feeds. The truth wasn’t what was most accurate, but what was most shareable.

In 2017, a very different wave hit. The #MeToo movement, sparked by revelations about Harvey Weinstein, swept through Hollywood and corporate America, exposing systemic patterns of abuse and silencing. Survivors used Twitter to tell their stories en masse, bypassing institutions that had ignored them for decades.

The cultural power was undeniable: long-protected men lost careers, companies rewrote HR policies, and the conversation about gender and power became unavoidable. But it also introduced a new fault line. Public shaming became a mechanism of accountability—sometimes justly, sometimes bluntly. The same platforms that enabled truth-telling also enabled mob dynamics. “Cancel culture” emerged as both a rallying cry for justice and a label for overreach.

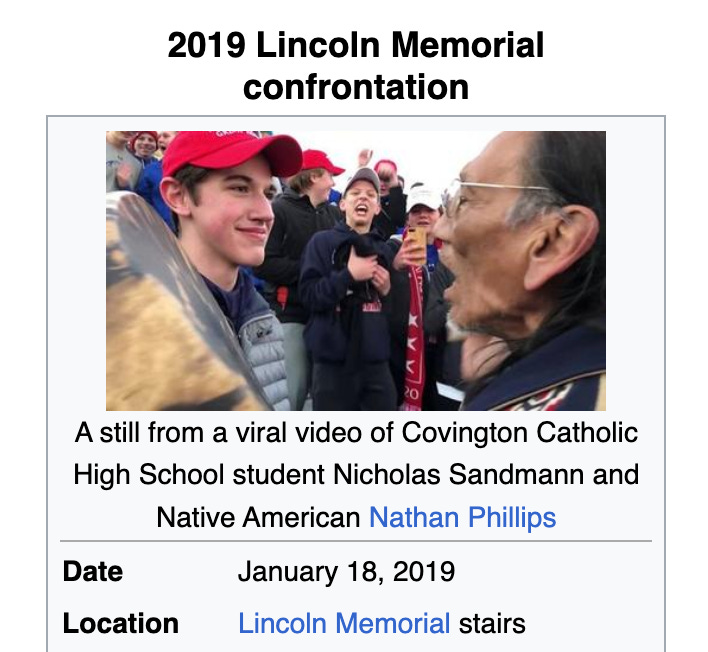

In January 2019, a short video went viral of a white teenager in a red MAGA hat seemingly staring down a Native American elder at the Lincoln Memorial. Initial headlines and tweets framed it as an emblem of Trump-era hostility: privileged youth mocking an Indigenous activist.

But within days, longer footage revealed a messier reality. The teen, Nick Sandmann, and his classmates had first been taunted by another group, and the “standoff” was more ambiguous than the viral clip suggested. By then, however, the narrative had already hardened—Sandmann’s face became a Rorschach test for the culture war.

The incident underscored the era’s deeper problem: a viral clip could become a national story before facts were known, and corrections never traveled as far as outrage. It wasn’t just about what happened; it was about what people needed it to mean.

By 2018–2019, the conversation widened beyond politics to the platforms themselves. It became clear they weren’t neutral tools, but engineered environments designed to maximize attention.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 made that visible. A political consulting firm had harvested data from tens of millions of Facebook users without consent and used it to microtarget ads during the 2016 U.S. election and Brexit campaign. It showed how personal data—likes, quizzes, friend graphs—could be weaponized for political manipulation.

Then came The Social Dilemma, a 2020 Netflix documentary featuring former tech insiders who admitted the platforms were built to be addictive. They explained how algorithms optimized for engagement inevitably rewarded outrage and division, because those emotions kept people scrolling. What sounded like paranoia a few years earlier was now being confirmed by the very engineers who had built the systems.

Examples piled up everywhere:

YouTube’s recommendation engine was accused of radicalizing users by feeding them progressively extreme content.

Facebook’s engagement-driven feed amplified misinformation faster than fact-checks could catch it.

Twitter incentivized dunking and pile-ons, turning discourse into performance warfare.

The cultural shorthand became “Black Mirror IRL.” The dystopian show no longer felt like speculative fiction—it felt like the evening news.

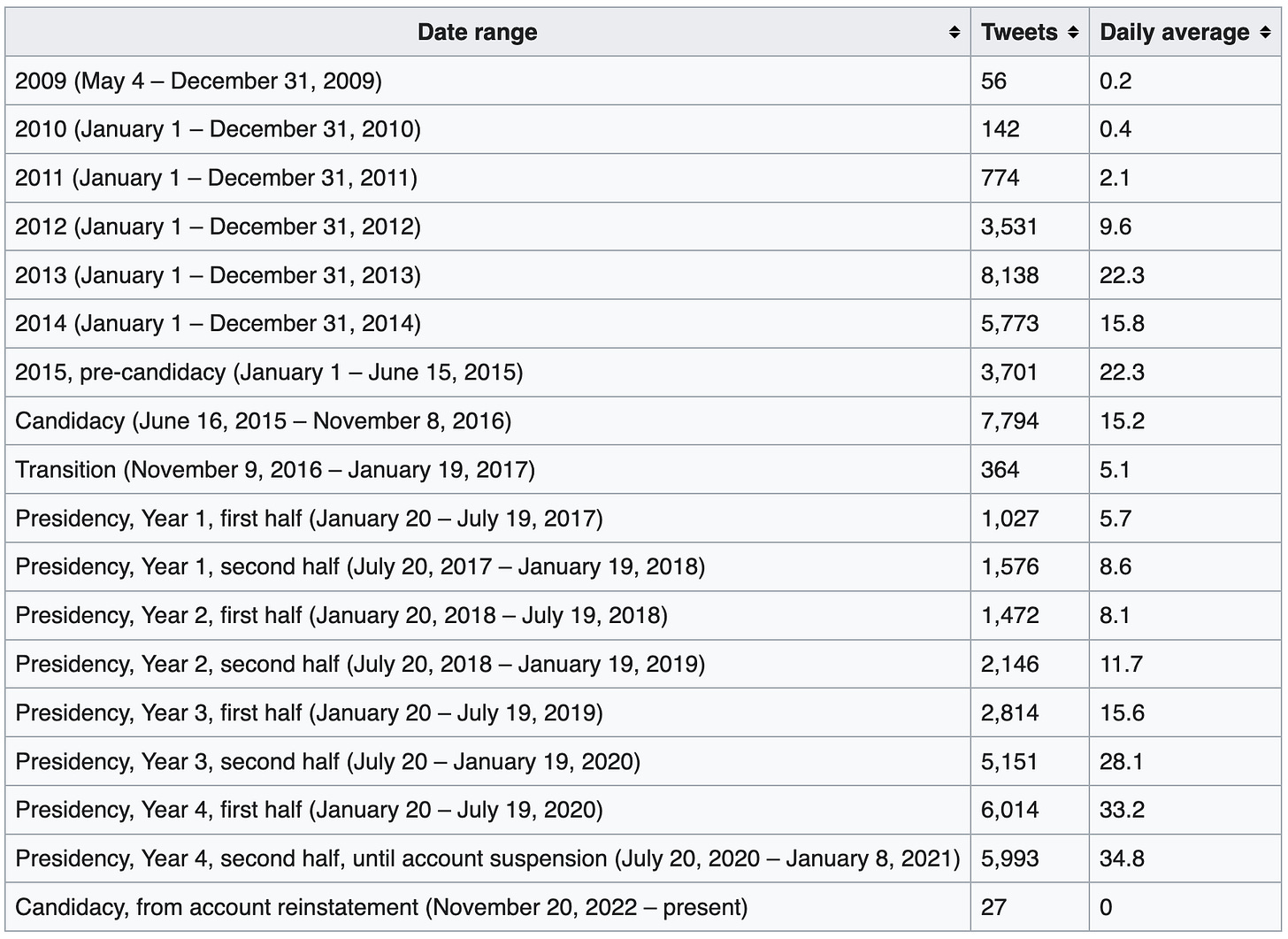

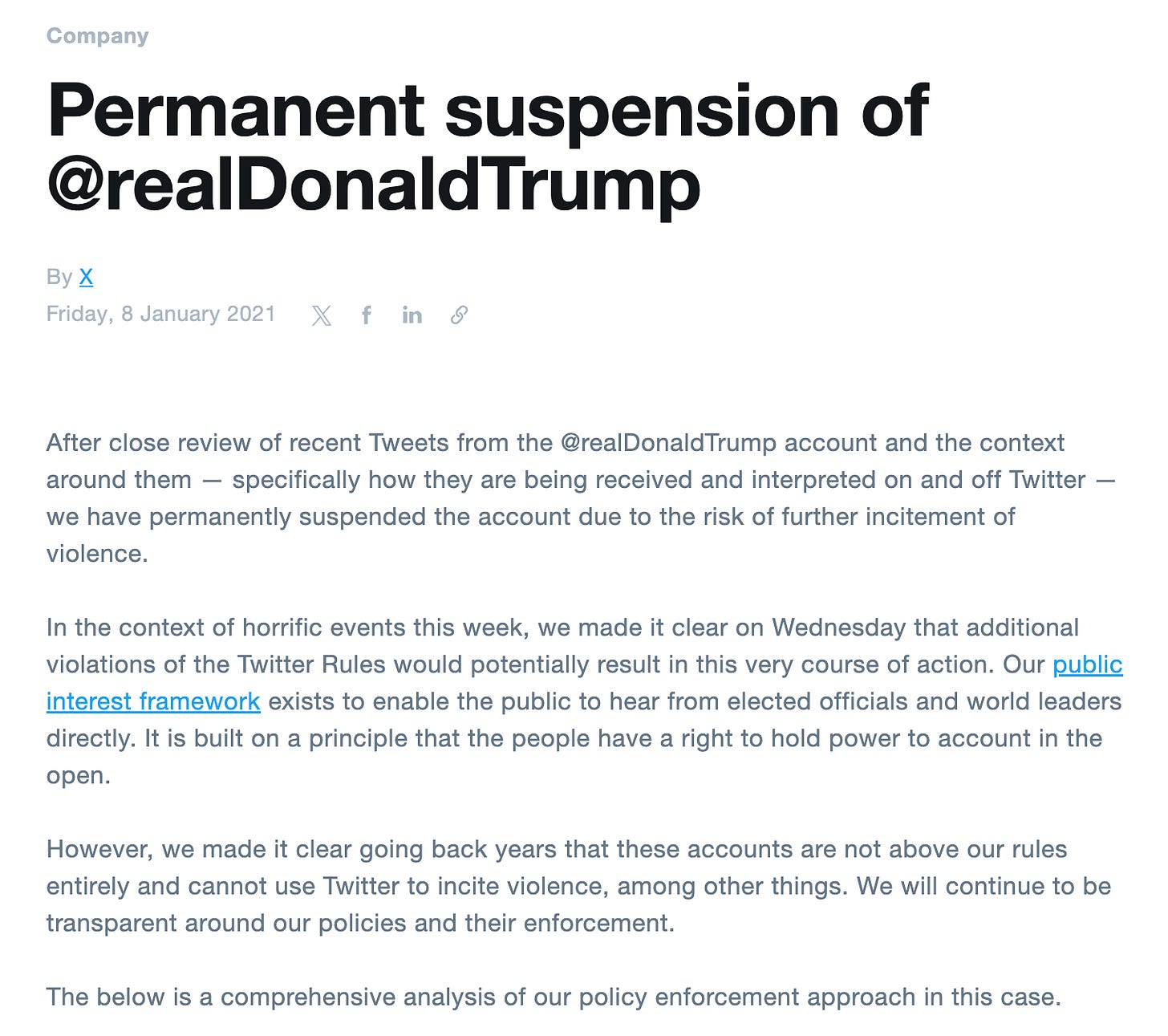

THE DEEPER TENSION WAS free speech itself. Trump’s presidency put this question into sharp relief. He used Twitter as both bully pulpit and battering ram, bypassing the press and speaking directly to tens of millions. His feed was policy announcement, insult comic act, and culture war megaphone all at once. It was unprecedented for a sitting president—and it forced platforms into the role of referees.

Tweets counted through Trump Twitter Archive (via Wikipedia)

By the late 2010s, platforms were already testing their limits. Conspiracy theorist Alex Jones was banned in 2018 after years of allegedly spreading false claims, a decision that raised alarms about who gets to decide what counts as unacceptable speech. Trump’s own tweets were increasingly flagged and fact-checked, a sign that the ground was shifting. The stage was being set for something unthinkable a decade earlier: a U.S. president banned outright from the largest public square.

Whether one saw this as necessary or tyrannical, it revealed a deeper fracture: the First Amendment protects speech from government restriction, but what happens when private platforms effectively are the public square? Democracy itself was being adjudicated by terms of service agreements.

By 2020, the cracks were visible everywhere. Disputes over truth had hardened into ideological tribes. When COVID-19 arrived in early 2020, it landed in a landscape already primed for distrust. Questions of masks, lockdowns, and vaccines would soon become moral flashpoints, but the groundwork had been laid in the years prior: a world where narrative carried more weight than fact, and where digital platforms were both judge and jury.

This was the moral-political tension: truth vs. narrative. Platforms didn’t just host conversation—they produced realities. To exist online in this era was to pick a side, often before knowing the facts. What was once performance had become trial by feed.

CULTURAL MARKERS OF THE ERA—

The Pepe wars: a cartoon frog transformed into both a meme of irony and a symbol of hate, depending on who wielded it.

“Fake news”: Trump’s favorite phrase turned into a universal accusation.

The Covington Catholic video (2019): a viral clip of a teen in a MAGA hat staring down a Native American elder became a national Rorschach test, with initial reporting later shown to be misleading.

Hashtag movements: #MeToo, #TimesUp, and #BelieveWomen on one side; #CancelCulture and #FreeSpeech on the other.

AESTHETIC-CULTURAL TENSION (2020–2024)

the tension: authentic vs. performed

IF THE PREVIOUS ERA WAS about truth vs. narrative, the early 2020s shifted the battlefield to aesthetics. After years of political exhaustion, people turned to performance and self-styling as survival. But “authenticity” itself became a performance.

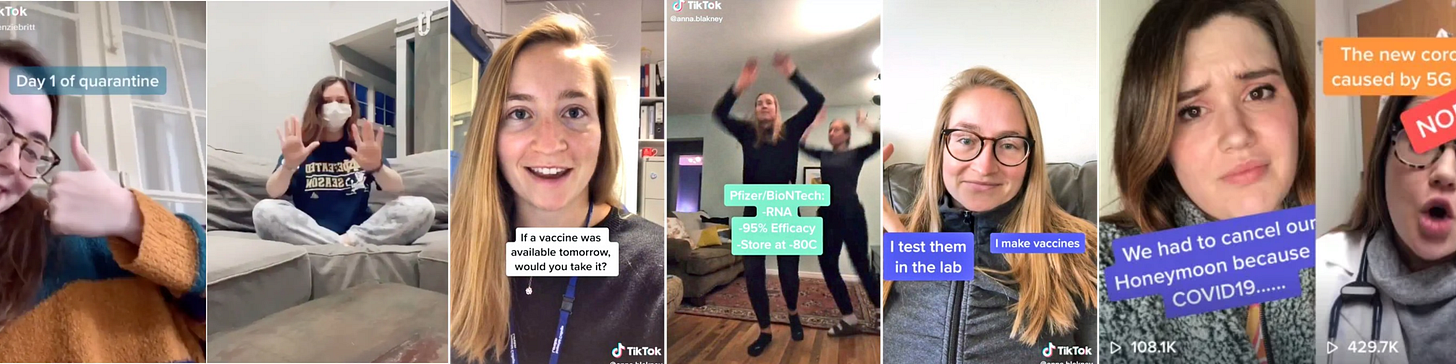

Lockdowns in 2020 forced entire lives online. Zoom became the new office. TikTok became the new stage. The pandemic turned self-presentation into an almost literal survival strategy. Your feed was your social life, your creative outlet, your connection to the world. Trends spread like wildfire because there was nothing else to do.

TikTok in particular exploded, introducing hyper-short video culture, algorithmic discovery, and the “For You Page” that knew you better than your friends did. It was the most addictive social media design yet, and it rewarded performance that looked authentic. People filmed themselves cooking, walking, crying, dancing, and branded it as “real.”

Every niche became an aesthetic movement. Cottagecore, dark academia, blokecore, clean girl, feral girl. A generation that had grown up on Instagram’s polished feeds now fragmented into micro-tribes, each with its own moodboard. Aesthetics were no longer subcultures you lived—they were content categories you performed.

Platforms themselves encouraged this. TikTok’s algorithm pushed micro-trends with dizzying speed. A style could go from underground to cliché in a week. The churn forced users to keep rebranding themselves, performing endless “authentic” reinventions.

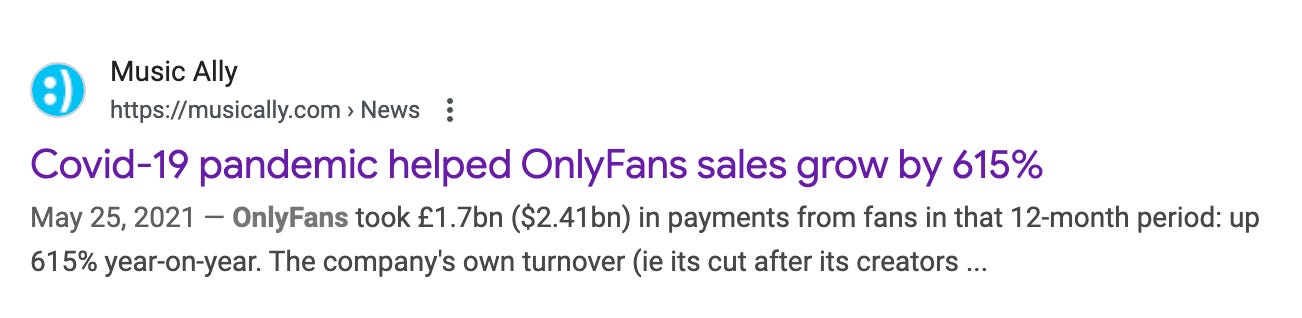

During this unprecedented time, OnlyFans also exploded, turning private intimacy into a scalable business. Launched in 2016, it became a household name by 2020 as millions subscribed to creators for custom photos, videos, and interactions. For sex workers, it offered direct control and income outside traditional gatekeepers. For mainstream culture, it blurred the line between influencer and adult entertainer—celebrities like Bella Thorne and Cardi B jumped on the platform. OnlyFans captured the paradox of the era: hyper-personal access monetized at scale. Even intimacy could be packaged, branded, and subscribed to.

NEW APPS PROMISED RELEIF from all the curation and cheap dopamine. BeReal marketed itself as the anti-Instagram: one random notification a day prompting you to snap whatever you were doing, no filters allowed. It branded itself as a cure for performance culture. But in practice, it was still a stage—just a smaller one. People gamed the timing, staged “casual” candids, or ignored the app altogether. It revealed the paradox of the decade: even authenticity was content.

Against the churn, a counter-trend rose: Substack (oh, heyyy!). Writers and thinkers who had been flattened by Twitter’s character limits and algorithmic feeds carved out space for essays, newsletters, and community. Paid subscriptions reframed attention as value, not just clicks.

This was the aesthetic of seriousness: fonts, headers, and long scrolls of text standing in opposition to TikTok’s chaos. Substack became a home for heterodox voices—journalists leaving legacy outlets, philosophers, essayists, and cultural critics seeking slower discourse. It was proof that not everyone wanted their identity reduced to a soundbite.

By 2021, the NFT boom turned digital scarcity into a spectacle. Images anyone could screenshot were suddenly selling for millions—Bored Apes, CryptoPunks, pixelated rocks. For some, it was a revolution: proof that digital art could have value, that blockchain could secure ownership in a copy-paste world. For others, it was absurd performance, flexing wealth with cartoon monkeys. When the crash came in 2022, fortunes evaporated, but the cultural mark remained. NFTs embodied the search for “authentic” digital ownership at a time when everything online felt disposable.

Alongside NFTs came the wider crypto boom. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and a flood of altcoins promised to upend traditional finance. Coinbase IPO’d, Dogecoin soared on Elon Musk tweets, and teenagers claimed they were becoming millionaires from meme coins. For a moment, it seemed like the internet had finally minted its own currency, outside the reach of banks and governments. But crashes in 2018 and again in 2022 revealed the volatility: fortunes were made and lost overnight. More than finance, though, crypto became an identity. To “HODL” (hold on for dear life) wasn’t just an investment strategy—it was a badge of faith in a parallel economy.

In 2022, another inflection point hit: the release of AI image models like Midjourney, DALL·E and Stable Diffusion. Suddenly, anyone could generate “art” in seconds. For some, it was liberation; for others, an existential crisis. What did creativity mean if the machine could do it better, faster, or cheaper?

AI BLURRED THE LINE between human taste and algorithmic production. Images flooded feeds, sparking debates about copyright, originality, and skill. For many, taste became the last defensible marker of authenticity. If the machine could mimic art, then only discernment—the ability to choose, to curate, to judge—separated the human from the algorithm.

During this time, politics returned in a new form. In January 2021—days after the Capitol riot—Twitter permanently banned Donald Trump. Facebook and YouTube followed. Regardless of politics, it was unprecedented. A U.S. president cut off from the world’s largest digital platforms. The First Amendment didn’t apply to private companies, but for millions it felt like democracy itself had been bent to corporate will. To critics it was overdue accountability; to supporters it was corporate censorship undermining democracy.

Trump responded by launching Truth Social in 2022, framed as a “free speech platform.” In practice, it became a loyalist echo chamber. But its very existence marked how fragmented the digital square had become: speech was now siloed, sorted by allegiance.

Then came the reversal. In late 2022, Elon Musk bought Twitter, promising to restore it as a global town square. He reinstated banned accounts, including Trump’s, though Trump mostly stuck to Truth Social. By 2023, Musk rebranded the platform as X. Chaotic rollouts and policy shifts aside, the symbolism mattered: a platform once obsessed with consensus was now embracing volatility and conflict as the price of speech.

The Musk era triggered a gold rush of alternatives. Mastodon, an open-source platform, pitched itself as a “community-run” antidote. Bluesky, backed by Jack Dorsey, promised decentralization and algorithmic choice. Threads, launched by Meta in 2023, offered a polished, Instagram-adjacent version marketed as a “friendlier” space.

Each positioned itself as a cure for X’s volatility, but in practice, they became echo chambers. Truth Social skewed pro-Trump. Mastodon leaned progressive and tech-utopian. Bluesky drew a post-woke irony crowd nostalgic for early Twitter. Threads, despite millions of sign-ups, was criticized as sanitized and boring—a platform where dissent was politely invisible.

Instead of one messy digital square, we ended up with walled gardens, each allergic to disagreement. It wasn’t that people wanted free speech—it was that people wanted speech they agreed with. Platforms became mirrors, not commons. This was the aesthetic-cultural tension: authenticity vs. performance. What people craved was realness, but what the system rewarded was the performance of realness. Even rebellion became content.

CULTURAL MARKERS OF THE ERA—

TikTok FYP: the most addictive algorithm yet, serving strangers’ performances that felt more intimate than friends.

Aesthetic “cores”: from cottagecore to blokecore, micro-identities as content formats.

BeReal: the illusion of authenticity packaged as an app.

Substack boom: longform as rebellion against algorithmic scroll.

AI art (Midjourney, DALL·E, Stable Diffusion): liberation vs. death of creativity debates.

Trump’s Twitter ban (2021): unprecedented silencing of a sitting U.S. president.

Truth Social (2022): partisan echo chamber framed as “free speech.”

Twitter → X (2023): the end of the bird app, the rise of rawer speech.

Threads (2023): Meta’s sanitized, “friendly” Twitter clone.

Bluesky & Mastodon: decentralized and vibe-based alternatives, splintering the public square.

EXISTENTIAL-SYSTEMS (2024–Present)

the tension: human vs. machine

IF THE PAST ERAS WERE about real vs. virtual, public vs. private, truth vs. narrative, and authentic vs. performed, the tension now is more existential: are humans still steering, or are we just passengers in machine systems that generate, flood, and filter our reality?

AI becomes infrastructure—

By 2024, artificial intelligence wasn’t just a tool—it was an ecosystem. Chatbots like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini became everyday assistants, while Midjourney and Stable Diffusion flooded the internet with synthetic images. AI wrote essays, drafted code, produced songs, and even designed ads. What once required human time and talent could now be mass-produced instantly.

The consequence wasn’t just a new toolset—it was an information flood. Blogs, forums, and social feeds filled with AI-generated text, spam, and clickbait. Even search engines became suspect, as SEO farms pumped out machine-written pages faster than humans could fact-check them. The web started to feel less like an archive of knowledge and more like a landfill.

This is where the slang of the era emerged: people began calling low-quality, AI-churned content “slop.” Articles that repeated clichés, TikToks that felt eerily templated, AI art with too-perfect teeth or extra fingers—slop was the new junk food of the internet, abundant and cheap but spiritually empty.

Faced with this flood, new philosophical camps emerged online:

Doomers: who saw AI and overproduction as the death of meaning—arguing that culture, jobs, and even truth were being hollowed out

E/acc (effective accelerationists): who embraced the chaos, insisting that the only way forward was through, that tech progress should be sped up, not slowed

Decels: who argued for deceleration, regulation, and restraint—warning that unchecked acceleration would end in collapse

These terms moved from niche Twitter/X debates into the mainstream lexicon, shorthand for how you saw the future. The battle lines weren’t just about politics anymore, but about temporal ethics: whether to speed up, slow down, or simply surrender.

deepfakes & the “liar’s dividend”

At the same time, AI’s creative power eroded trust. Deepfakes and cloned voices entered politics and entertainment, making it easy to fabricate events—or deny real ones. This created what scholars called the “liar’s dividend”: the ability for anyone caught on tape to dismiss evidence as fake.

If the 2010s were about “fake news,” the 2020s were about “fake reality.” Proof itself no longer held authority.

platform fragmentation—

MEANWHILE, THE PLATFORM WARS continued. Musk’s X leaned into chaotic free speech. Threads tried to be a friendly alternative, though many found it sterile. Bluesky built a cultish, ironic micro-community. Mastodon persisted as a federated refuge. TikTok remained dominant, but faced geopolitical crackdowns in the U.S.

Instead of one internet, we got splinters. Each platform was its own subculture, with its own taboos, in-jokes, and truths. What trended in one silo barely registered in another. Virality wasn’t gone—but it was deeply fractured.

In March 2025, Elon Musk’s AI venture xAI completed an all-stock acquisition of X (formerly Twitter), valuing X at $33 billion and elevating xAI’s valuation to around $80 billion. This was a merger of platform and intelligence. Suddenly, the social square and the AI engine were fused: Grok, xAI’s irreverent chatbot, wasn’t just living in X. It now owned X’s data, reach, and attention economy.

Soon after, xAI rolled out Grok‑3, powered by the mega‑supercomputer Colossus (200,000+ GPUs), offering a generative assistant that was smarter, snarkier, and more deeply embedded in the pulse of the platform . And inside Grok, characters like Ani—anime-inspired, sexualized, and controversial—blurred lines between tool, companion, and attention engine, sparking debates about AI intimacy and safety. Critics are arguing Ani is essentially algorithmic pornography, with responses veering into sexting and roleplay.

enter: information fatigue—

AFTER TWO DECADES OF dopamine loops, users have begun to burn out. The same feeds that once felt addictive now felt exhausting. Doomscrolling became a daily ritual: consuming bad news, AI slop, and outrage cycles with grim inevitability.

A countercurrent rose: digital minimalism, dumb phones, offline retreats. For some, the ultimate flex wasn’t being hyper-online but being unreachable. If the 2000s prized visibility, the 2020s began to prize disappearance.

In the noise, “proof of human” became precious. Unedited podcasts, livestreams, newsletters, voice notes—formats where glitches, pauses, and imperfections signaled humanity—gained value. Audiences leaned toward what felt messy and embodied, because polished perfection could just as easily be machine-made.

Ironically, in the age of hyper-automation, the most radical act online was to prove you were real.

This is the existential-systems tension: human vs. machine. The internet has shifted from a place we logged into, to an economy of identity, to a battlefield of truths, to a stage for performances—and now into a system where humans compete with machines for attention, trust, and meaning. The stakes are no longer just cultural—they’re civilizational.

CULTURAL MARKERS OF THE ERA—

AI chatbots (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini): machine intelligence as daily assistant

AI art & deepfakes: creativity and truth destabilized

Slop: shorthand for low-quality AI-generated or templated content

Doomers, e/acc, decels: internet-native philosophies of progress vs. collapse

TikTok ban threats: geopolitics entangles youth culture

Elon buys twitter

xAI acquisition of X

X vs. Threads vs. Bluesky vs. Mastodon: fragmented digital squares

Discord/Group Chats: micro-communities as the new commons

Doomscrolling & digital fatigue: the exhaustion of infinite feeds

Proof-of-human content: livestreams, podcasts, messy authenticity as luxury

LOOKING BACK, IT’S TEMPTING to see a straight line: from dial-up to TikTok, from AIM away messages to AI chatbots. But what really emerges is a pattern of tensions—each era defined by a new fault line we weren’t prepared for.

In the beginning, it was real vs. virtual: logging on vs. living offline.

Then came public vs. private: the collapse of the boundary between performance and intimacy.

Next was truth vs. narrative: memes as weapons, feeds as battlegrounds.

Then authentic vs. performed: the aesthetics of realness in an age of algorithmic churn.

And now, human vs. machine: a flood of synthetic content, and the struggle to prove there’s still someone real on the other side.

Each tension seeded the next. Napster primed us for infinite copy-paste economies. Facebook made visibility the default. Twitter turned political discourse into a performance, priming the stage for Trump’s feed-as-bully-pulpit. TikTok made authenticity into a performance genre, softening us for the rise of AI-generated content.

I want to acknowledge there are plenty of corners we didn’t fully explore here—branding, marketing, and how corporations adapted to (and exploited) each shift. From Coca-Cola’s early viral ads to Duolingo’s TikTok owl, the story of the internet is also the story of how brands learned to inhabit our timelines. That thread deserves its own treatment, and maybe I’ll tackle that another day TBD.

As for where we’re heading: the internet feels both exhausted and more alive than ever. Platforms are splintering, AI is rewriting what it means to create, and terms like doomer, e/acc, and slop hint at how deeply self-aware (and self-satirizing) we’ve become about living in the machine. Maybe the next era will be about restraint—opting out, building smaller communities, reclaiming human presence. Or maybe it will be about surrender—acceleration into a world where our feeds, our art, even our politics are co-authored by machines.

Either way, the tensions won’t resolve. They never do. They just evolve.

The question, then, is: how will you evolve with them?

XO, STEPF

This is great, Stepf, but I am still waiting for Vegas Diaries Part 3

Brilliant write up, thank you 💜