We've developed the strangest relationship with time, and it's breaking something essential about how humans create meaning.

There's a peculiar ache that defines our current moment—not just the speed at which culture moves, but the way that speed has taught us to experience loss before we've even had the chance to experience presence. We're nostalgic for viral moments that happened last Tuesday, wistful about futures that feel simultaneously inevitable and already expired, mourning experiences while they're still unfolding. The traditional gap between living and remembering has collapsed into something more immediate and more hollow.

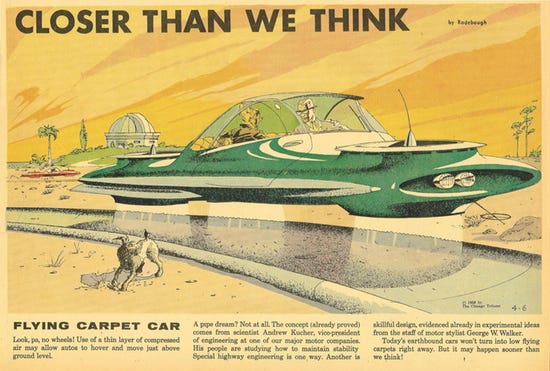

This phenomenon has roots in something deeper than internet culture. We carry within us the accumulated disappointment of previous generations' unfulfilled promises—the flying cars that never materialized, the gleaming cities we were supposed to inhabit by 2000, the space-age optimism that now exists only as aesthetic nostalgia. When we encounter the confident curves of 1960s futurism, we experience a particular kind of loss: not just for those specific dreams, but for the psychological capacity that could generate such unambiguous hope.

Mid-century imagination possessed something we seem incapable of accessing—the ability to project forward without the protective armor of irony or preemptive disappointment. Progress felt linear, technology benevolent, the future comprehensible. Those visions were never really about tomorrow; they were expressions of present anxieties projected forward as solutions. But they emerged from a consciousness that still believed in its own capacity to imagine beyond complexity.

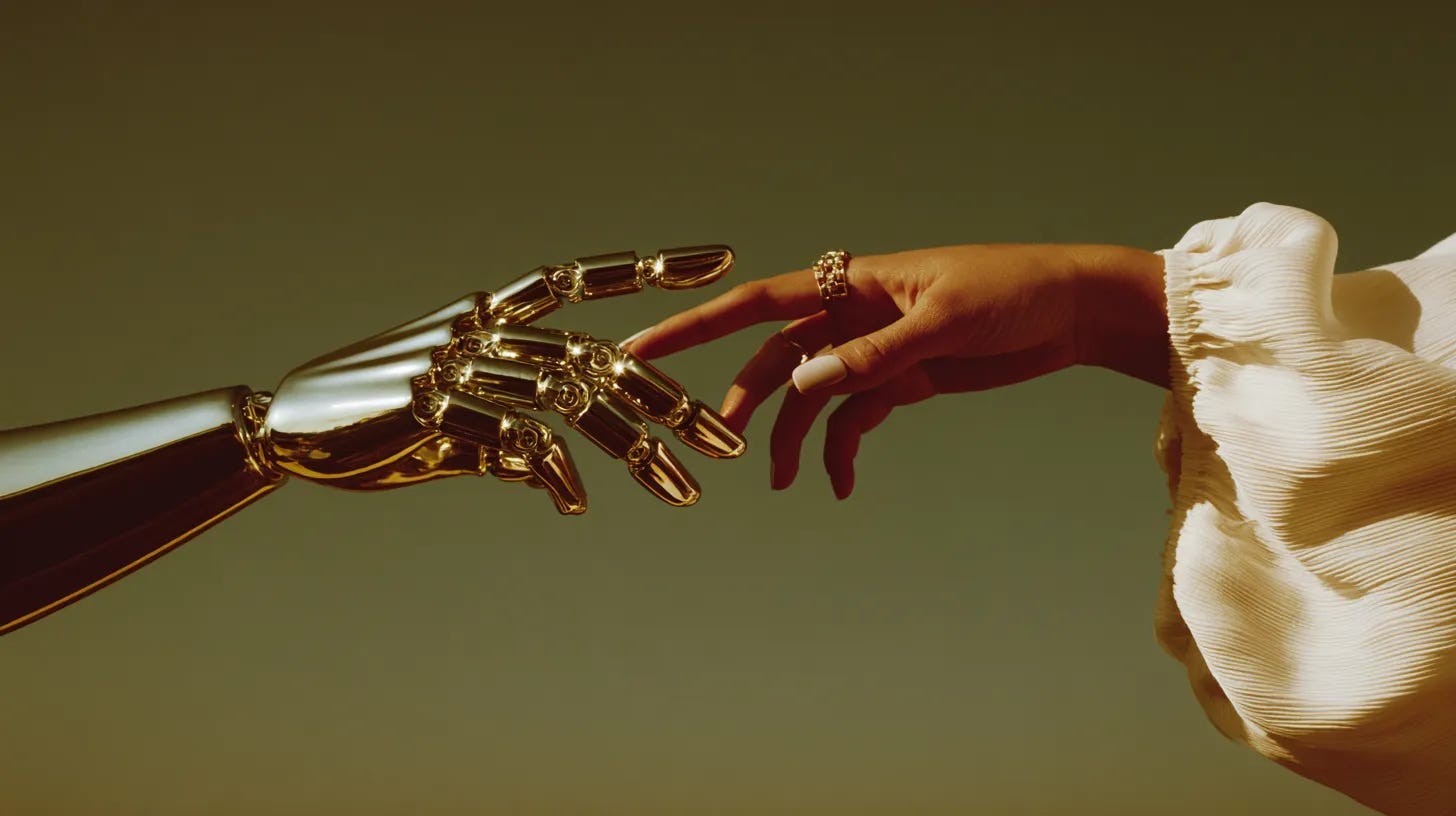

What we've inherited isn't just their failed predictions, but a more fundamental skepticism about the possibility of genuine hope. We've learned to approach emerging possibilities—AI breakthroughs, climate solutions, technological promises—with a kind of premature reminiscence, already mourning them from some imagined future vantage point where they've transformed everything and nothing simultaneously.

But something more disturbing is happening in our immediate present. The internet has taught us to compress the entire emotional lifecycle of cultural experience into windows that used to be occupied by single moments. We discover, saturate, and nostalgically abandon shared phenomena within timeframes that preclude any real depth of engagement.

Consider the rhythm of meme culture: a dance, a phrase, a collective digital moment arrives with the force of revelation. For a brief window, everyone speaks the same language, shares the same references, breathes together in algorithmic synchronicity. Then, almost immediately, that same moment recedes into background noise, becoming a relic we can barely remember participating in. Two weeks later, references to it carry genuine nostalgic weight, as if we're encountering artifacts from a lost civilization.

This isn't just cultural acceleration—it's the systematic destruction of the conditions necessary for meaning to develop. Significance requires time to accumulate, context to mature, reflection to deepen understanding. Instead, we've created an environment where cultural objects achieve emotional weight not through persistence or contemplation, but through the sheer intensity of collective attention followed by inevitable abandonment.

The meme operates as both symptom and accelerant of this temporal compression. Designed for maximum replication and minimum longevity, each viral moment carries within it the seeds of its own obsolescence. We're already mourning it while we're participating in it, because we understand, almost instinctively, that its lifespan is measured in attention cycles rather than lived experience.

What emerges is a form of cultural poverty disguised as abundance. We've become experts at extracting nostalgic value from increasingly brief encounters with shared meaning, but this expertise comes at the cost of our capacity for sustained engagement. Every scroll becomes a small act of temporal displacement, a brief meeting with the recent past that already feels impossibly distant.