signal vs. noise: why people go out of their way to hate your work

the frontier tax and the mathematics of creative displacement

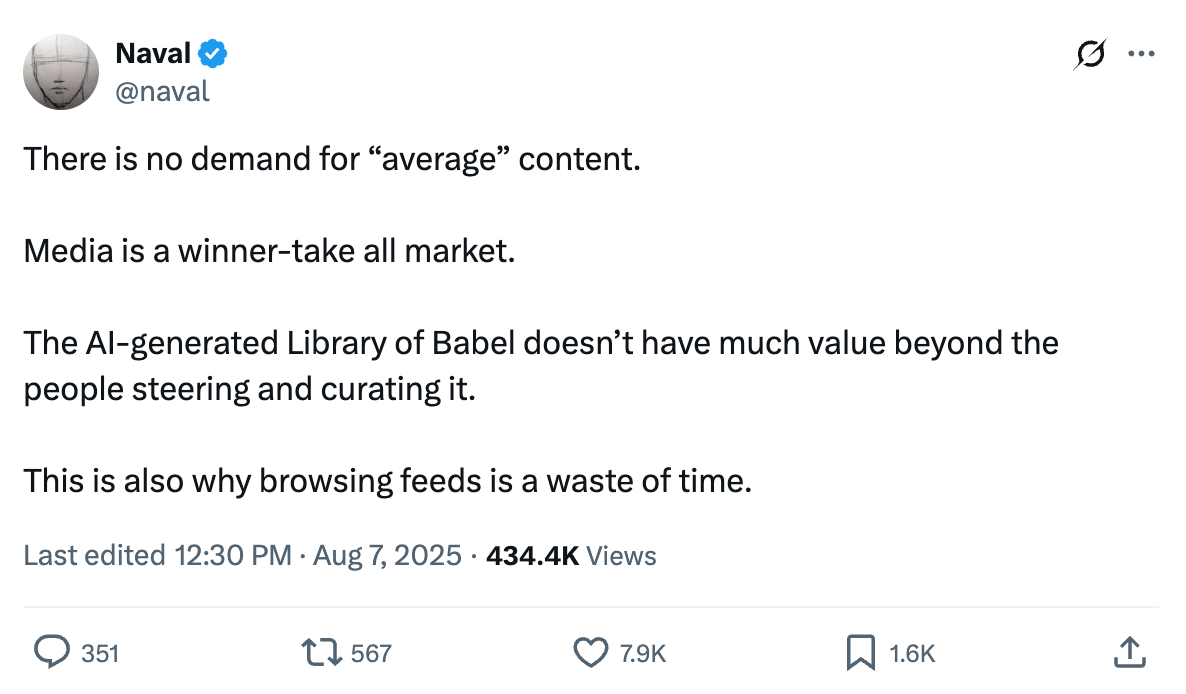

There's an interesting mathematics to creative displacement that most people refuse to acknowledge. Earlier this week, when Naval tweeted that "there is no demand for 'average' content" and that "media is a winner-take-all market," he articulated something that makes a lot of creatives and writers deeply uncomfortable: the brutal arithmetic of creative competition in an age of technological augmentation.

I know this discomfort intimately. As someone who openly uses AI for synthesis and editing, I've become a lightning rod for a particular brand of creative resentment. The attacks come predictably from Substack's decel contingent—writers who've convinced themselves that AI represents some existential threat to creativity, authenticity, or the environment. They seek out work that openly embraces technological tools, not to engage with ideas, but to perform outrage for their audiences. They screenshot, restack, and rally their followers around a shared mythology: that technological augmentation somehow cheapens human creativity.

But here's what they're missing: their hatred isn't noise. It's signal. And it's the most valuable signal you can receive about whether you're actually onto something important.

Every paradigm shift creates what I’m calling "the frontier tax"—the inevitable backlash against early adopters who threaten existing hierarchies. This isn't incidental; it's structural. The intensity of the hatred correlates directly with the power of the displacement.

When Bob Dylan plugged in his Fender Stratocaster at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, the crowd didn't just disagree—they booed with religious fervor. "Judas!" someone screamed from the audience. The folk purists weren't just defending musical tradition; they were defending their entire identity as arbiters of authentic expression. Dylan's electric guitar represented an existential threat to their cultural gatekeeping.

The same pattern emerges across creative history. When Impressionist painters began using pre-mixed paints from tubes instead of grinding pigments by hand, the academic establishment didn't merely critique their technique—they excluded them from the Salon for decades. The convenience of tube paints wasn't just a procedural change; it democratized color access and enabled plein air painting. The old guard recognized the threat immediately.

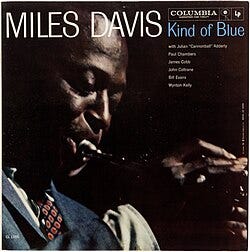

Miles Davis faced similar fury when he introduced electric instruments to jazz. Traditional purists declared it wasn't "real" jazz anymore. They were right, in a sense—it was something more expansive, more powerful, more resonant with contemporary audiences. Kind of Blue didn't kill acoustic jazz; it created fusion and opened entirely new creative territories.

The pattern holds: technological augmentation doesn't replace human creativity—it amplifies it, scales it, and makes it accessible to people who were previously excluded from the conversation.

the mathematics of displacement—

Naval's insight about winner-take-all markets reveals the psychological substrate of anti-AI resentment. In any creative field, there's a pyramid: a small number of exceptional creators at the top, a larger group of competent professionals in the middle, and a vast base of average practitioners at the bottom. Technological tools don't affect these groups equally. They compress the middle while expanding the top.

Consider what happens when AI-assisted writing becomes mainstream. The writer who was "pretty good" at research, synthesis, and editing suddenly finds themselves competing against writers who are "pretty good" at those same skills but augmented by tools that make them significantly more efficient, more thorough, and more capable of handling complex projects.

The gap isn't just about speed—though AI can accelerate research and first-draft generation by orders of magnitude. It's about cognitive bandwidth. When I use AI to handle routine synthesis tasks, I free up mental energy for higher-order thinking: structural innovation, argumentative nuance, conceptual breakthroughs. The AI doesn't think for me; it handles the cognitive grunt work so I can think more clearly.

This creates what economists call "skill-biased technological change." The tools amplify existing capabilities rather than replacing them entirely. A mediocre writer with AI assistance is still mediocre—they just produce mediocre content faster. But a skilled writer with AI assistance becomes genuinely formidable.

The resentment makes perfect sense. If you're competing primarily on effort rather than insight, on time spent rather than value created, technological augmentation represents an existential threat to your comparative advantage.

why resonance can't be faked—

The most revealing aspect of anti-AI rhetoric is how it fundamentally misunderstands what creates value in creative work. The critics act as if the process—the grinding, the struggling, the manual labor of writing—is what gives work its worth. They've confused suffering with value creation. But audiences don't care about your process. They care about resonance.

If a piece of writing changes how someone thinks about the world, if it crystallizes an insight they couldn't articulate, if it moves them to action or deeper understanding—does it matter whether AI helped with the research? Does it matter whether the first draft came from a human brain or a language model that was then refined, restructured, and infused with human insight?

The obsession with "pure" human creation reveals a romantic fallacy about how creativity actually works. All writing is collaborative. We build on previous ideas, synthesize from multiple sources, and refine through iterative editing. The notion that introducing AI into this process somehow taints the final product assumes that human creativity operates in isolation—which has never been true.

Shakespeare didn't invent his plots; he borrowed, adapted, and synthesized from existing sources. T.S. Eliot famously said "good poets borrow, great poets steal." The value wasn't in originality of source material but in the quality of synthesis and expression.

What AI changes is the scale and speed of this collaborative process. Instead of being limited to the books on my shelf or the research I can personally conduct, I can synthesize insights from vastly larger knowledge bases. Instead of spending hours on routine editing tasks, I can focus on the creative and strategic decisions that actually matter.

the historical pattern of resistance to integration—

Every transformative tool follows a predictable adoption curve, marked by initial resistance, grudging acceptance, and eventual integration. The resistance phase is characterized by three consistent arguments:

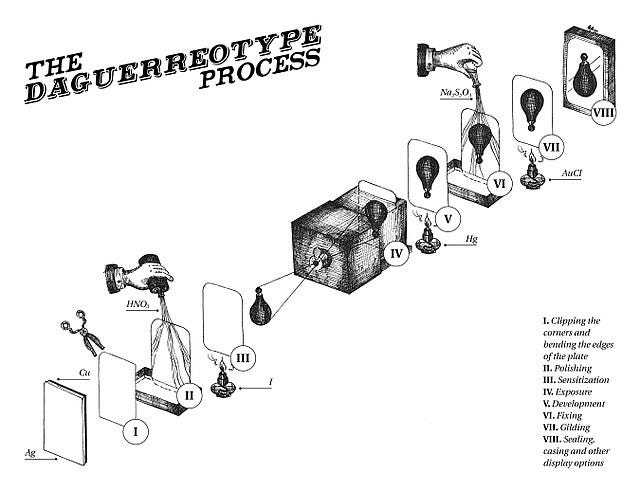

"It's not authentic." Early photographers were dismissed as technicians rather than artists. The camera was seen as a mechanical shortcut that bypassed the "real" skill of painting. Now photography is recognized as its own art form, with its own aesthetics and masters.

"It's too easy." When digital audio workstations made music production accessible to bedroom producers, established musicians complained that "anyone could make music now." They were right—and that democratization led to an explosion of musical innovation, from hip-hop to electronic music to bedroom pop.

"It eliminates human skill." Word processors were supposed to make writers lazy. Calculators were going to atrophy mathematical thinking. GPS would destroy our sense of direction. In each case, the tool eliminated routine tasks and freed human capacity for higher-order functions.

The pattern suggests that our current AI resistance will follow the same trajectory. Today's anti-AI purists will be tomorrow's adopters, once the competitive disadvantage becomes too severe to ignore.

Understanding this pattern transforms how you interpret creative backlash. When people seek out your work specifically to hate on it, when they organize their audiences around opposing your approach, when they treat your methods as a threat to their identity—you're paying the frontier tax.

This tax is not incidental; it's confirmation that you're operating in genuinely new territory. If your approach were obviously wrong or ineffective, it would be ignored rather than attacked. The intensity of the opposition correlates with the power of the threat you represent to existing hierarchies.

The decel creatives attacking AI-assisted creation aren't really concerned about creativity or authenticity. They're defending their position in a hierarchy that's being rapidly reorganized. Their expertise in traditional writing processes—their ability to grind through research, their tolerance for tedious editing, their familiarity with legacy tools—suddenly matters less in a world where AI can handle much of that cognitive labor.

Their resentment is understandable. But it's also irrelevant.

signal vs. noise—

The key insight is learning to distinguish between signal and noise in creative feedback. Most criticism is noise—reactive, emotional, defending existing structures. But the fact that people are seeking out your work to criticize it, is signal.

Noise looks like:

Attacks on your methods rather than engagement with your ideas

Emotional language about "cheating" or "authenticity"

Attempts to rally audiences around shared opposition

Focus on process rather than outcomes

Signal looks like:

People changing their behavior in response to your work

Adoption of your methods by other practitioners

Concrete results and measurable improvements

Expansion of what's considered possible in your field

The most important signal is resonance. If your writing consistently generates engagement, changes minds, and creates value for readers, the process critique becomes irrelevant. The market doesn't care about your creative purity; it cares about whether your work solves problems, provides insights, or creates beauty.

We're living through a profound transformation in creative work, and the transformation is inevitable. The writers, artists, and creators who embrace technological augmentation while maintaining their unique human insight will consistently outperform those who cling to traditional methods out of principle.

This doesn't mean abandoning human creativity—it means understanding what human creativity actually consists of. The value isn't in the manual labor of research and editing. It's in the conceptual frameworks, the emotional intelligence, the strategic thinking, and the unique perspective that only humans can provide.

AI handles the grunt work. Humans handle the vision.

The frontier tax is real, but it's temporary. The resentment will fade as augmented creation becomes normalized. What remains is the competitive advantage of those brave enough to pay the tax early.

I, for one, am happy to pay the tax.

XO, STEPF

I remember the good old days, when writers, real writers, would spend their day chiseling each syllable into stone, and then came papyrus. You call that writing? Back then, it took strength and stamina to complete a sentence. Now, anyone with a reed and some ink can record their thoughts. The gods will not be pleased.

Great article, Stephanie. In my opinion, the whole question surrounding the use of AI in the writing process is already moot. Like you, I simply don't give a fuck about what other people think about the so-called authenticity of the process. In fact, I am more interested in learning how to use the tool to tell a better story. In my case, I have discovered that in working with ChatGPT to write a scene, I am the story architect, and GPT is my personal assistant with whom I work to build the scaffolding before I write the scene. It's like having a developmental editor participate in the writing process as early as the first draft. Why toil away in my lonely garret when I can engage a resource that helps weigh out the value of each beat in each scene? Moreover, I am writing science fiction that incorporates some of today's scientific controversies. Imagine being able to discuss the relevance of the Law of Increasing Functional Information as it applies to the plot and characters in my story, and the "person" has my plot outline and character arcs already stored in memory, actually knows what I am talking about, and is available 24/7. Given the choice of using this resource or staying stuck in the identity mind trap of what it means to be a real writer, please shut the fuck up and leave me alone.

I know you're taking a lot of flak for "coming out" and rebutting the tired arguments of the old guard, but someone's got to do it, and you're doing a great job! Thanks.

Omg Stepfanie, you are lowkey leading a new movement in thought over here. Love it. You’ve gotten SO MUCH unnecessary flak for literally no good reason.

And as someone who participated in that flak—by leaving dismissive comments on notes—I just want to say I’m sorry. Happy to say I stand corrected.

I hope you can accept my apology and also accept my newly paid subscription as a token of peace. Even tho it’s just an excuse to unlock even more of your AMAZING WRITING 🤩