Taylor's most boring era: The Life of a Showgirl

a smooth, highly produced album full of songs that slid right past me

I didn’t expect to have strong opinions about The Life of a Showgirl, but after listening to the album all the way through, I found myself sitting in silence wondering how something with so much anticipation, polish, and pedigree could feel so strangely inert. I’ve never considered myself a Swiftie, but I’ve always respected her work. Over the years, I’ve enjoyed her albums in different ways. Some as background noise, others as emotional companions, and a few as genuine artistic achievements. This one, though, left me with nothing to hold on to.

It wasn’t that I hated it… it’s that there was no visceral reaction at all. No moment that made me wince or roll my eyes. I wasn’t disappointed in the dramatic sense; I was just surprised by how little of it lingered. The production was fine. The lyrics were fine. The whole thing felt technically accomplished but emotionally flat. And I guess that contrast between the scale of the operation and the hollowness of the impact was interesting enough to make me want to write this.

I’m the same age as Taylor Swift—just a few months off. We grew up in parallel, though obviously on very different stages, and for better or worse, I’ve tracked her career almost in tandem with the phases of my own life. I always felt that subtle background hum of identification, the way her albums lined up with the timing of my real life: teenage heartbreak, identity shifts I couldn’t yet articulate, the blur between how I felt and how I wanted to be perceived, big romantic swings, moments of defiance, little seasons of quiet transformation. Even if I wasn’t living the same specifics, the emotional map made sense.

Her lyrics were dramatic and often over-explained, but they also had that quality that good writing has—precision through specificity. She wrote like someone actively becoming herself, and I think a lot of us followed along not just because of the music, but because the becoming felt real. A line would land and stick because it felt like she had lived it exactly as you had. That was her gift.

There was a kind of lyrical intensity she carried through each phase—sometimes sharp and specific, sometimes broad and sweeping, but always emotionally legible. She wasn’t afraid to write directly from the inside of an experience, even when it was messy or unflattering, and I think that was what made it stick.

Which is why The Life of a Showgirl caught me so off guard. Not because it’s bad. It isn’t. If anything, it’s clean and competent and carefully styled. The sound is polished. The visuals are crisp. The narrative is coherent. It just didn’t move me. For the first time since I was a teenager, I listened to a Taylor Swift album and felt nothing in particular. The lyrics didn’t catch. The melodies didn’t haunt. Even the parts that were clearly meant to dazzle felt like they were going through the motions. I didn’t dislike it… I just didn’t feel it.

Part of what I’ve always admired about Taylor is that she never let her writing coast. Even in her most commercial eras, the work still had edges. There was tension in the lyrics, some emotion or contradiction being worked out in real time. She wrote like someone who couldn’t not write. And at the same time, she scaled. She turned a confessional songwriting style into a global empire—all without giving up control. That duality—deeply personal lyrics delivered at massive scale—has always been part of the magic. And that’s something I respect just as much as the music. Her work ethic is extreme. She didn’t just make hits; she built a system. A brand. A universe. And she did it while navigating an industry that rarely lets women keep the rights to their own names, let alone their masters. She earned her seat and kept it.

In that regard, Taylor Swift is not just an artist. She is a brand, a micro‑economy, a force of nature. That much is impossible to ignore. Her Eras Tour shattered records: it became the highest‑grossing concert tour in history, pulling in over $2 billion from more than 10 million ticket sales. That alone makes her a kind of infrastructure: stadiums, vendors, road crews, merch factories, transportation networks, venue staff, local economies—she moves real money, real people, real jobs.

Her net worth is estimated today at around $1.6 billion, a status she achieved largely through music, touring, catalog control, and smart business decisions rather than side ventures. She became the first artist to reach ten‑figure status based on her songwriting and performance rather than just branding or product lines. Her catalog, streaming deals, merchandise, licensing—all of it layers together into a ruthless vertical integration.

She also sets industry benchmarks. She is the only artist to have had seven albums debut at over a million in first week U.S. sales. She holds a slew of records (Grammy counts, Billboard feats, streaming records) that turn her discography into data points of dominance. Every time she reclaims masters, or release strategy shifts, or she drops subtle Easter eggs that drive social media speculation, that is part of the engine. The brand is taut, responsive, meticulously managed.

But she’s also a real person. And maybe that’s what makes her latest album so oddly hard to place. The Life of a Showgirl arrived with all the usual fanfare—Spotify billboards, theorizing fans, beautifully executed visuals—but for me, something just didn’t click. I’ve listened to every one of her records since we were both teenagers, and this was the first time I walked away feeling nothing in particular. Not angry, not disappointed, just… untouched. The lyrics didn’t land, the themes didn’t pull me in, and even the joy—if that’s what it was aiming for—felt out of reach.

I think we might be watching what happens when the machine has been running too hard for too long. It’s not that the songs feel hollow because she’s too famous, or too rich, or too safe—it’s that she might just be tired. Not uninspired, not past her prime—just deeply, recognizably tired. And it shows. Not in sloppiness, but in tone. The new album doesn’t feel like it’s reaching for anything. It feels like it’s exhaling. It’s not sharp, not aching, not curious—it’s just… fine. Maybe even content. But even the contentment sounds defensive, like she’s trying to prove she’s okay more than she’s letting herself be.

And that’s where it loses me. Not because I need drama or heartbreak, but because the emotional current that used to run underneath her writing feels muted. But maybe that’s just what happens when you’ve spent two decades giving people every version of yourself. Maybe at some point, the only story left to tell is how exhausting it is to be the story at all.

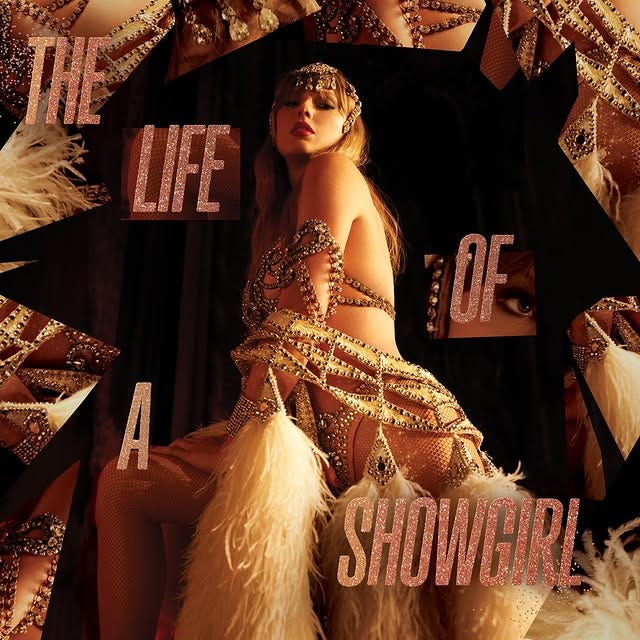

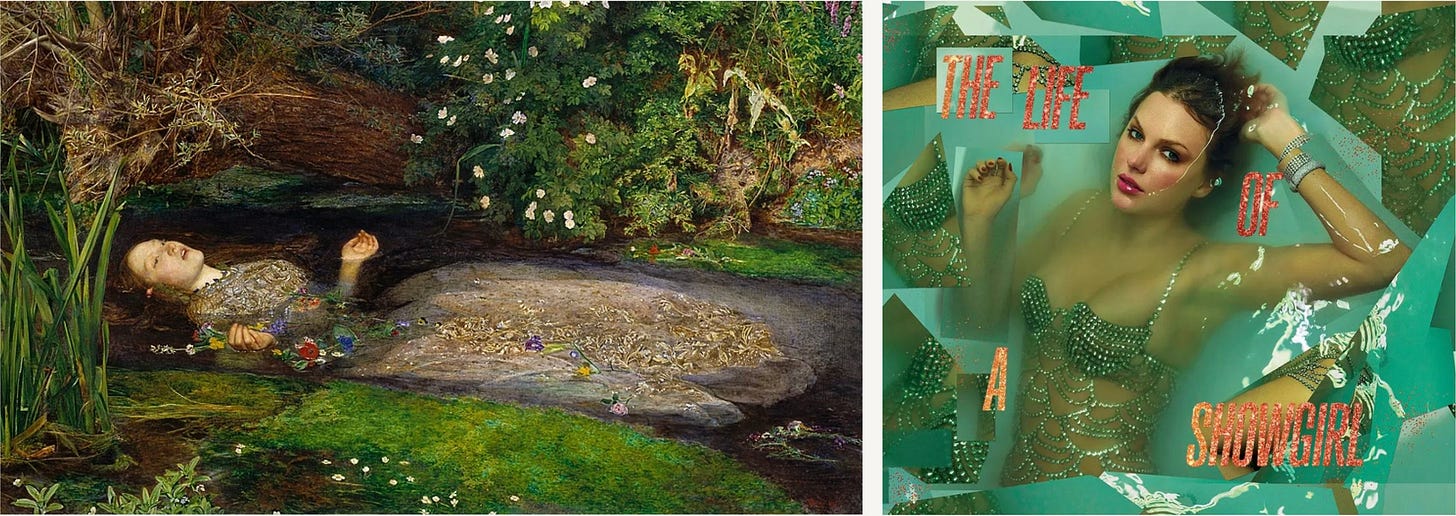

The opening track is titled “The Fate of Ophelia,” and the album’s cover art mirrors that reference almost too perfectly. The wet hair, jeweled makeup, and floating pose is a clear nod to John Everett Millais’ iconic painting of Ophelia, moments before she drowns. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Ophelia is young, overwhelmed, and undone by a world that asks too much of her. She becomes beautiful in her unraveling. That image—soft, tragic, controlled—feels like a thesis for the whole album. It’s not just a visual; it’s a metaphor for the performance of collapse. Aestheticized, palatable, frozen. Even when referencing emotional devastation, everything remains intact. That’s the story this album seems more interested in telling.

There’s something oddly unrelatable about the content this time around. Many of the songs touch on fame, public perception, media narratives, and the exhaustion of being constantly seen. I don’t doubt the reality of that pressure. I don’t doubt that she feels isolated, misread, unfairly judged. But for a listener who isn’t famous, that kind of theme starts to wear thin. Her best songs used to translate her experiences into something universally felt. This album feels more like it’s reporting live from a life very few of us will ever inhabit. Most people aren’t famous. So when you build an entire album around the themes of backlash, spectacle, and mythologized versions of yourself, you risk building something emotionally inaccessible. Not because it’s too complicated, but because it’s too self-referential to translate.

Are you a Taylor fan? Did you like this? Am I missing something? Am I crazy???

This album just doesn’t carry the same lyrical intensity that used to define her writing. I don’t think she’s out of touch or creatively bankrupt. But she does seem… strangely unburdened. That might sound like a good thing—after all, isn’t happiness what we’re all supposed to be aiming for? But as a writer, I’ve noticed that certain states of mind just don’t yield the same kind of raw material. When you’re in pain, or transition, or even deep curiosity, you reach inward for meaning. That tension shows up in language. You write toward clarity because you don’t already have it. But when you’re content—or when your contentment has calcified into self-protection—there’s less urgency to say anything that cuts.

What made Taylor Swift’s earlier work resonate wasn’t that we shared the same experiences. It was that she could take her very specific experiences and write them in a way that felt like a mirror. Songs like “All Too Well” or “Enchanted” or even “The Archer” weren’t universal in content, but they were universal in tone. They tapped into longing, regret, self-doubt—the kind of emotional friction that makes lyrics stick. In contrast, The Life of a Showgirl feels like it’s trying to be understood more than it’s trying to understand. It narrates her life, but it rarely invites the listener in.

To be fair, maybe that’s the point. Maybe The Life of a Showgirl is meant to be more theatrical, more aesthetic than emotional. Maybe it’s supposed to reflect the distance between who she is and who people think she is. But if that’s the case, it still leaves something hollow. Because even her past reinventions—Reputation, Lover, Folklore—contained some kind of vulnerability, some emotional grit beneath the concept. This one feels like a set with no back wall.

None of this changes how impressive the machine is. If anything, it makes it more impressive that she’s held it together this long. But for the listeners who came to her music for that precise emotional grip—the sharp line, the quiet confession, the wound with a name—it’s hard not to notice when that part goes missing. The Life of a Showgirl might be a triumph of image, but it never quite opens the door. It just felt like a smooth, highly produced album full of songs that slid right past me.

It’s not a bad album. It’s just not one I’ll return to. For an artist who built her legacy on emotional precision, this one felt oddly distant—like watching someone narrate their life from behind glass. I’m sure it’ll break streaming records. I’m sure it’ll soundtrack a million TikToks. But for me, it ended where it started: polished, protected, and ultimately, boring and forgettable.

—S

PS: today’s the last day to lock in an annual sub for 50% off, forever :)

a fall care package from me to you: what to read, cook and try this season

ICYMI: I’m offering my biggest discount ever on all new annual subs through the weekend. I likely won’t do another discount this steep until next fall, so if you’ve been on the fence about subscribin…

I’m not a Swiftie by any stretch of the imagination but my daughters play her albums on repeat and I’ve definitely enjoyed her songs in the same way you describe here. I’ve seen things online that suggest everything you mentioned is intentional - that this is her way of putting on the performance her fame essentially has come to demand of her and that she’s burning it all down. It’s much better articulated in a post like this one:

https://www.instagram.com/p/DPVDpi7Db5y/?igsh=c3J0ZnUxaDFoOTFz

I’m not usually one for philosophizing about T Swift meanings and part of me wonders if the line of thought in the IG post is a reach but I also find it fascinating and it does seem like the sort of thing she’d do. If you read it, I’d be curious of your thoughts!

This essay articulates my “it’s fine” sentiment way better 😂 My feelings about this album have more to do with everyone’s reactions to it than the album itself, tbh. Not everything has to be a think piece (edit: this is not aimed toward this essay!) or deep analysis of lyrics. You can feel just “meh” about an album and move on with your life.