the art of creating your own reality

artist spotlight: Paul Gauguin (France, 1848-1903)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together.

(Previous muses: Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau // upcoming: Berthe Morisot)

today’s muse: Paul Gauguin (France, 1848-1903)

There's a moment in every creative person's life when they have to choose: paint the world as it "should" be, or paint it as it feels. Most people choose should. They paint grass green and skies blue and faces the color faces are supposed to be. They follow the rules, meet expectations, stay within the lines of good taste.

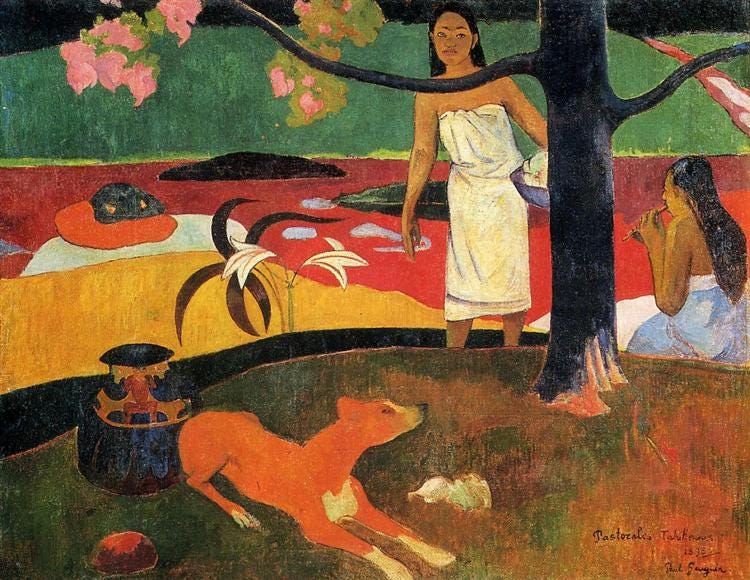

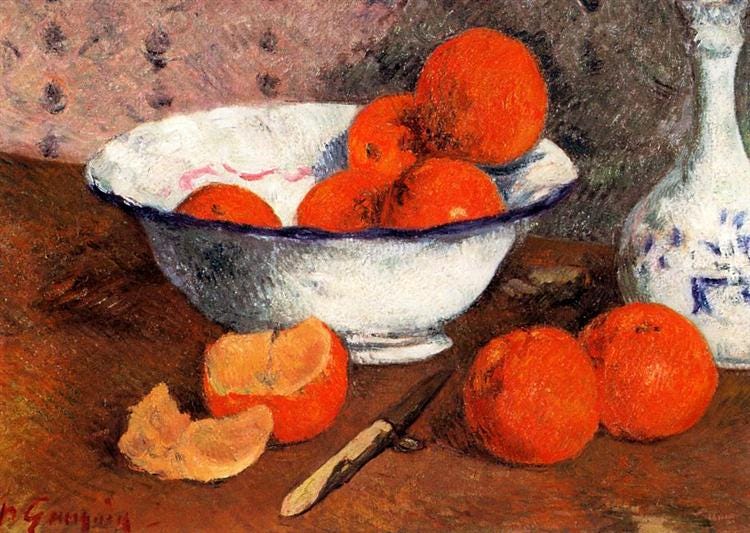

Paul Gauguin painted Christ yellow. He painted grass red and skies pink and women in hues that belonged more to feeling than to fact—color not as description, but as emotional charge. He abandoned a comfortable banking career, left his family, and sailed to the other side of the world chasing a vision that existed nowhere but in his head. His paintings look like what would happen if Anthropologie had existed in 1888 and decided to redecorate reality.

This isn't a story about finding yourself—it's about the courage to invent yourself completely. To trust your own eyes over everyone else's expectations. To believe that your version of beauty matters more than anyone else's definition of correct.

I've been thinking about Gauguin lately because his story feels like the logical next step after my piece exploring Henri Rousseau's creative audacity. Where Rousseau painted jungles he'd never seen, Gauguin went further—he painted places he'd been but made them look like his dreams. Where Rousseau was accidentally revolutionary, Gauguin was deliberately so. He looked at the art world's rules and said: what if I just... didn't?

This is a story about how Paul Gauguin became my patron saint of trusting your own weird taste—the courage to use the "wrong" colors, to paint what you feel instead of what you see, and to believe that your vision of the world might be more true than reality itself.

It’s worth noting, Gauguin’s mythos isn’t without complications. His vision of Tahiti as a primal paradise has been widely critiqued for romanticizing colonial settings while ignoring the real impacts of French imperialism. He also engaged in relationships with underage Tahitian girls—an unsettling fact often omitted from aesthetic retrospectives but necessary to acknowledge alongside the art.

the making of a revolutionary—

Paul Gauguin wasn't supposed to become an artist. Born in 1848 in Paris to Clovis Gauguin, a journalist, and Aline Chazal, daughter of the socialist writer Flora Tristan, he seemed destined for middle-class respectability. When Paul was just one year old, his father died suddenly while the family was traveling to Peru to escape political upheaval in France. His mother took Paul and his sister to live with wealthy relatives in Lima, where they spent four formative years surrounded by a culture completely different from bourgeois France.

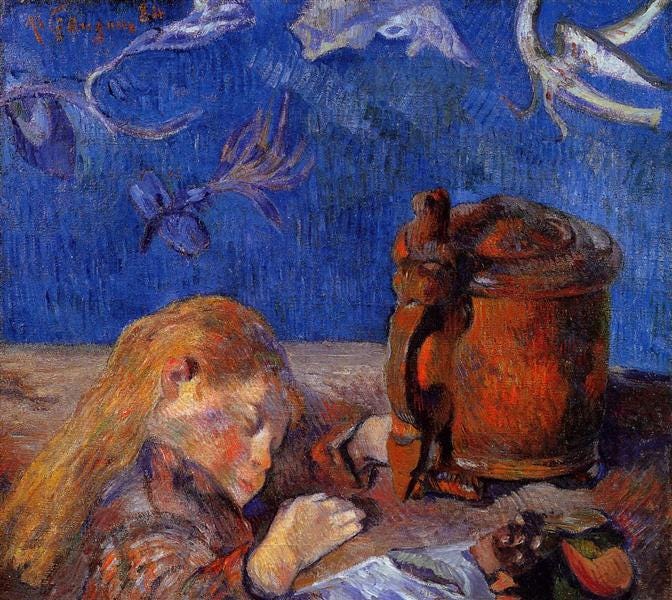

Those early years in Peru left an indelible mark on young Paul—the colors, the light, the sense of being somewhere exotic and far from European conventions. When the family returned to France in 1855, Gauguin would spend the rest of his life trying to recapture that feeling of being somewhere else, somewhere more vivid and alive.

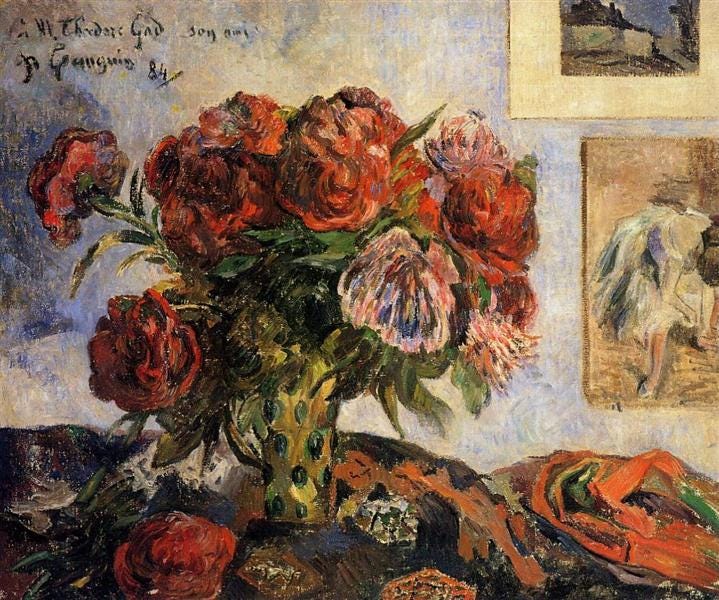

By his twenties, though, he had settled into exactly the kind of bourgeois life his background predicted. He worked as a stockbroker at the Paris Bourse, married a Danish woman named Mette-Sophie Gad in 1873, and began accumulating the markers of middle-class success: a comfortable apartment, five children, and a growing collection of Impressionist paintings that he bought on weekends as a hobby.

Gauguin was good at his job—he made excellent money during the boom years of the 1870s, enough to support his family in style and indulge his passion for collecting art. He bought works by Pissarro, Cézanne, Manet, and Degas, spending what today would be tens of thousands of dollars on paintings. But he wasn't just collecting—he was studying, learning, beginning to paint himself under the informal guidance of Camille Pissarro.

"I have always said that painting is the most beautiful of all arts," he later wrote. "In it, all sensations are condensed; contemplating it, everyone can create a story at will and with just one glance, the soul fills with the most profound memories."

the great abandonment—

The stock market crash of 1882 changed everything. The bank where Gauguin worked failed, and suddenly the comfortable life he'd built was in jeopardy. But instead of finding another banking position when the market recovered, Gauguin made a decision that would shock his wife, his friends, and respectable society: he would become a full-time artist.

"I have decided to paint every day," he told Mette in 1883. The decision was as much economic calculation as artistic calling—he genuinely believed he could make money selling paintings. He was wrong about the money, catastrophically wrong, but right about everything else.

Mette was horrified. They had five children to support, a household to maintain, social obligations to meet. "You are not a painter," she told him flatly. But Gauguin had seen something in art that he couldn't find anywhere else: the possibility of creating a world that made sense to him, even if it made no sense to anyone else.

The transition was brutal. The family's comfortable lifestyle evaporated almost overnight. They moved to cheaper quarters, sold possessions, borrowed money. In 1884, desperate to cut expenses, they moved to Copenhagen to live with Mette's family. The Danish bourgeoisie treated Gauguin like a curiosity at best, a failure at worst. He tried to make money selling French canvas, giving French lessons, anything to support his family while still painting.

"My painting doesn't catch on with the public," he wrote to his friend Émile Schuffenecker in 1885. "But I am quite sure that I'll be proved right in the end. I have such confidence in my art that I'd rather starve than give it up."

Brittany and the birth of a vision—

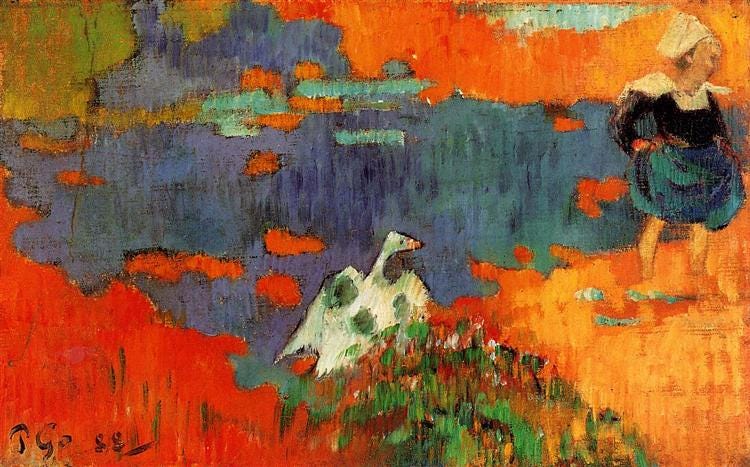

In 1886, broke and increasingly estranged from his wife, Gauguin made his first trip to Pont-Aven, a small artist colony in Brittany. The village was cheap—a crucial consideration—but also offered something Gauguin craved: distance from Parisian art world expectations and immersion in a culture that felt more authentic, more rooted in tradition.

"I love Brittany," he wrote. "I find the wild and primitive here. When my wooden shoes ring on this granite, I hear the muffled, dull, and powerful tone that I seek in my painting."

The Brittany years were transformative. Surrounded by younger artists who looked up to him—Émile Bernard, Paul Sérusier, and others—Gauguin began developing the theories that would revolutionize his art. He preached what he called "Synthetism": the idea that art should synthesize memory, emotion, and observation rather than simply copy nature.

"Don't paint too much from nature," he advised his followers. "Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, but think more of creating than the final result."

Vision After the Sermon (1888) shows the breakthrough. Breton women in traditional white bonnets witness Jacob wrestling with the angel, but the entire scene takes place on a field of pure red. Not reddish dirt or red-tinged grass—just red. Flat, impossible, completely invented red. When he showed the painting to local priests, hoping they might hang it in their church, they rejected it as too strange, too unnatural.

Gauguin didn't care. "I have painted what I see in the peasants' faces," he explained. "The simplicity and superstitious nature of these people." The red field wasn't meant to represent actual ground—it was the color of vision itself, of spiritual experience that transcends ordinary reality.

the Vincent interlude—

In October 1888, Gauguin traveled to Arles to paint with Vincent van Gogh, who had been begging his friend to join him in the south of France. Van Gogh idolized Gauguin, called him "the painter of painters," and believed they could create a revolutionary artistic community together.