There’s a pattern you start to notice if you spend enough time watching innovation play out in public: the people who end up being right almost always sound unhinged at first.

They propose things that seem too big, too fast, too weird. They get laughed at, dismissed, or aggressively downplayed. And then five or ten years go by—and suddenly everyone talks about them like they were obvious all along.

This isn’t a coincidence. It’s a feature of how large systems metabolize new ideas. The more original the insight, the more threatening it feels to anyone invested in yesterday’s frameworks. Not because it’s wrong. But because it forces a reassessment of assumptions they’d rather keep intact.

In a world optimized for predictability, novelty feels like chaos.

Most people are trained to filter for familiarity. They call it common sense. But what they really mean is consensus. Ideas that are legible to existing models. Solutions that make sense within the current paradigm.

But by definition, paradigm-shifting ideas don’t fit the current model. They break it. That’s why they matter.

This is why visionaries almost always meet institutional resistance first. Not because they’re wrong, but because they’re speaking in a future dialect. The people listening don’t understand the reference points yet, so the idea gets downgraded to noise.

By the time it’s obvious, it’s already too late to lead with it.

"When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong." — Arthur C. Clarke

Large institutions (governments, universities, legacy media, Fortune 500s) don’t exist to chase truth. They exist to preserve internal order. They filter ideas through risk, liability, reputation, and precedent.

And that makes them allergic to the unknown.

Even when people inside these systems are smart, their incentives aren’t aligned with originality. They get promoted by maintaining coherence, not by questioning core assumptions. They’re judged by performance under known constraints, not by their ability to invent new ones.

That’s why genuinely disruptive ideas often look like a downgrade at first. They aren’t polished. They don’t have clean data sets or case studies. They don’t fit in a white paper. But that doesn’t make them wrong. It makes them early.

Which is exactly what legacy systems are least equipped to recognize.

The term “disruptive innovation” was coined by Clayton Christensen in the 1990s. He used it to describe new technologies that didn’t start out better than incumbents—but that eventually outpaced and replaced them. They entered the market through unconventional channels. They served different users. And over time, they rewrote the rules.

That’s what real visionaries do. They don’t tweak the system. They exit it. Then they build something stronger in its place.

The original phrase “movers and shakers” came from a poem by Arthur O’Shaughnessy in 1873: “We are the music-makers, / And we are the dreamers of dreams... / Movers and shakers / Of the world forever, it seems.” It wasn’t about politics or fame—it was about those who shape the future through imagination. Those who move the world by refusing to stay inside its current rules.

Elon Musk and SpaceX

When Elon said he was going to land a rocket vertically, the aerospace establishment laughed. NASA engineers called it a fantasy. Major media outlets mocked it. Even insiders in aerospace scoffed at the timelines, the goals, and the confidence.

But while legacy contractors burned through billions with little to show for it, SpaceX operated like a startup: rapid iteration, tight feedback loops, and an internal culture of engineering truth over protocol.

Now, the Falcon 9’s vertical landing isn’t just real—it’s routine. They’ve completed over 300 launches and reused boosters over 20 times each. Elon didn’t disrupt aerospace by applying for permission. He disrupted it by building faster than the bureaucracy could respond.

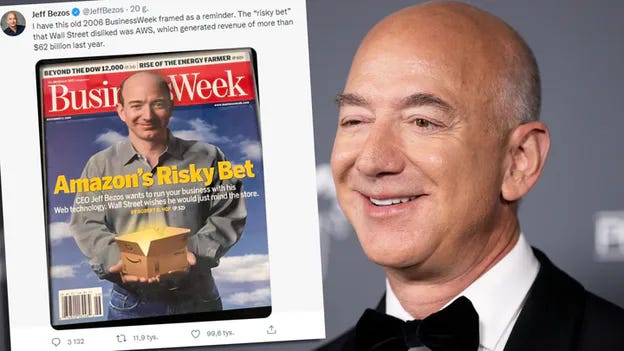

Jeff Bezos and AWS

In the early 2000s, Jeff Bezos pitched Amazon’s board on the idea of offering computing infrastructure as a service. At the time, this sounded bizarre. Amazon was a bookseller. Cloud computing wasn’t even a mainstream term. Why would anyone outsource their servers?

But Bezos saw it differently: every developer was building the same back-end scaffolding just to launch a simple app. So he created the rails underneath the internet.

AWS quietly launched in 2006. By 2023, it was generating $80 billion in revenue. It didn’t just disrupt how companies hosted websites. It fundamentally rewrote what it meant to scale a business.

John Carmack and Oculus

John Carmack, a legendary programmer in the gaming world, took a career detour into virtual reality when most people still associated VR with clunky prototypes and failed tech demos.

Carmack didn’t care. He saw a path no one else did—one based on improving latency, motion tracking, and immersive experience through brute-force engineering.

Oculus was eventually acquired by Facebook for $2 billion. But more importantly, Carmack’s technical vision laid the foundation for a real, scalable VR ecosystem. And yet even today, people still joke that VR is dead—while the infrastructure continues to grow quietly under the surface.

You don’t have to look far into history to see the same pattern play out again and again.

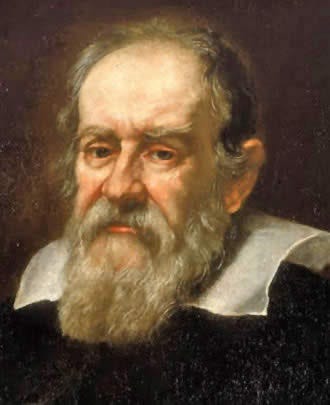

Galileo challenged the geocentric model of the universe and was sentenced to house arrest by the Catholic Church.

Socrates was executed for “corrupting the youth” of Athens because he encouraged people to question authority and think critically.

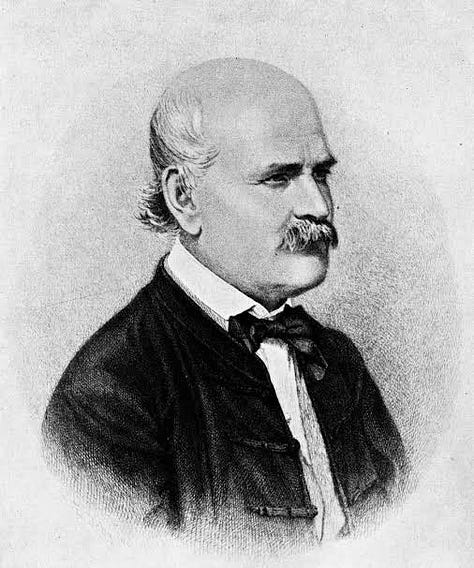

Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician, suggested that doctors wash their hands to prevent infection. He was mocked, ignored, and eventually died in an asylum. Years later, germ theory proved him right.

Being early has always looked like being crazy. And in systems that are more interested in preserving order than discovering truth, the visionary is always the first to be punished.

"All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident." — Arthur Schopenhauer

If you are someone building something unusual, early, or hard to explain—this is your permission slip to keep going. Resistance doesn’t always mean you’re wrong. Sometimes it means you’re playing a game that hasn’t been invented yet.

And if you’re evaluating new ideas? Don’t just ask, “Does this fit what I already know?”

Ask: What would have to be true for this to work?

It’s a much better filter for the future.

Because the biggest ideas always sound a little dumb at first. That’s how you know they’re new.

The below is a quote I return to often—a friendly reminder to be unreasonable.

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” — George Bernard Shaw

Like we talked about awhile back on X - "The first guy through the wall always gets bloody" - Moneyball.

You’re opening line is so friggin bang on true it’s not even funny ):