the revolutionary act of *just existing*

artist spotlight: Berthe Morisot (France, 1841-1895)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together. (Previous muses: Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin)

today’s muse: Berthe Morisot (France, 1841-1895)

You don't need to paint war scenes to be radical. You don't need to depict gods or revolutions or flaming lions in order to matter. Sometimes the most subversive thing you can do is paint a woman brushing her hair. A girl reading. A room with too much light.

Berthe Morisot didn't try to impress anyone. She didn't paint to win arguments. She painted to capture what was already slipping away—the private, unrecorded moments that never make it into history books. She painted women as they were, not as they were posed. And in doing so, she created a body of work that still feels more honest than much of what came after it.

I've been thinking about Morisot lately because her story feels like an antidote to the noise. In our age of performance and optimization, when every moment needs to be content-worthy and every experience needs to be documented for maximum impact, there's something deeply radical about her approach: paint what you see, not what you think people want to see. Value the quiet moments. Trust that presence, captured honestly, is enough.

This is a story about how Berthe Morisot became my patron saint of revolutionary ordinariness—the courage to believe that the interior world deserves a place on the canvas, and that beauty, when painted honestly, doesn't need explanation.

Born in 1841 in Bourges to a well-to-do bourgeois family, Berthe Morisot moved to Paris as a child and grew up in exactly the kind of comfortable circumstances that were supposed to produce accomplished wives, not professional artists. Her father was a prefect, her mother came from a family of successful architects. Painting was encouraged—as a hobby. A genteel accomplishment, like speaking French or playing piano.

But Morisot and her sister Edma were restless. By their twenties, they were studying under established artists, copying masters at the Louvre where women were allowed to learn but never lead, and pushing against the boundaries of what was considered appropriate for young ladies of their class.

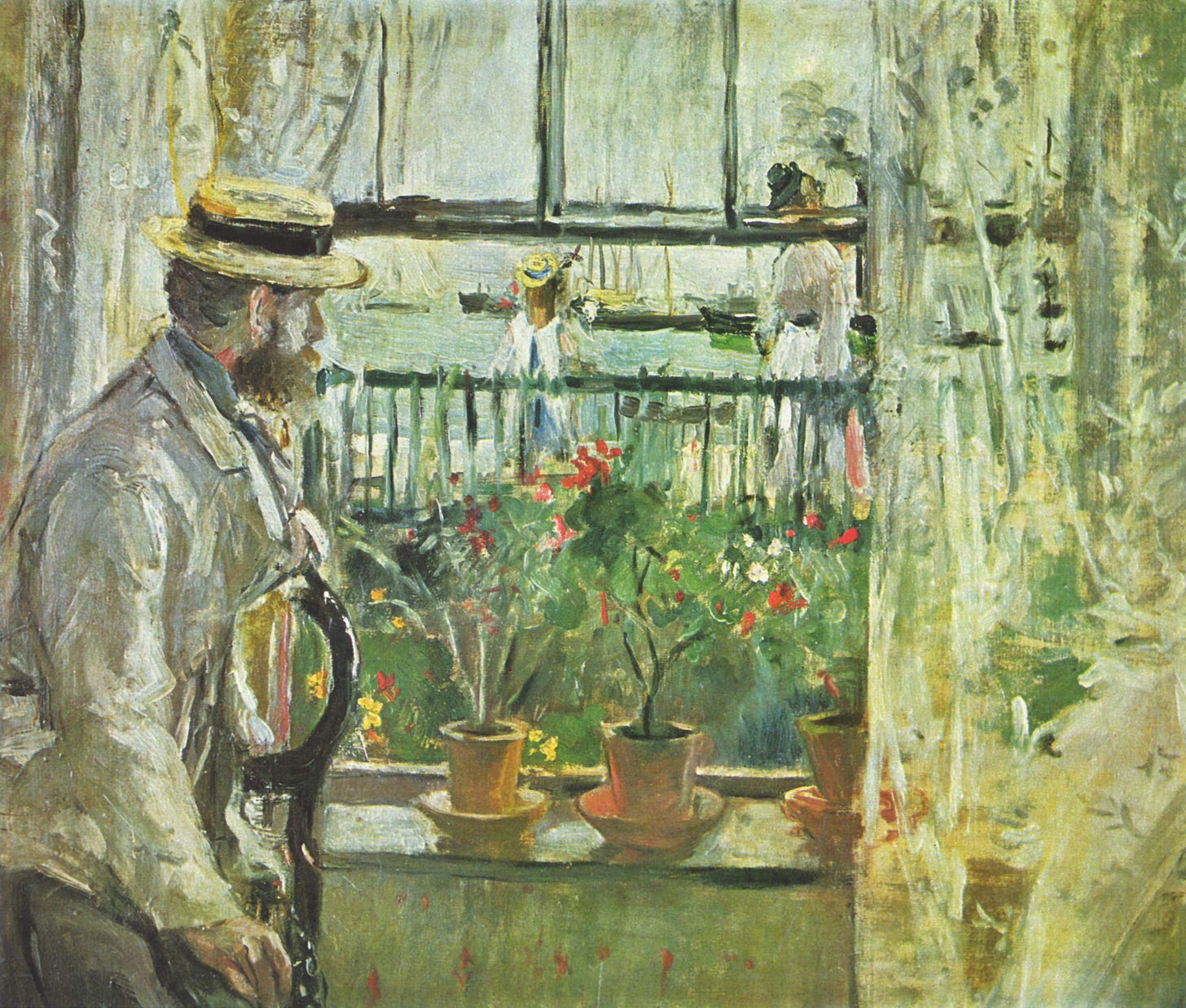

Everything changed when Morisot met Édouard Manet in 1868. She was twenty-seven, already developing her own artistic voice, and Manet recognized something in her work that went beyond amateur accomplishment. She began posing for him—appearing in eleven of his paintings—but more importantly, she became part of his circle. Through Manet, she met Monet, Renoir, Degas, the artists who were developing a new way of seeing that would challenge everything the art establishment believed.