the patient revolutionary: the art of sustained attention

artist spotlight: Camille Pissarro, St. Thomas/France (1830-1903)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together.

(Previous muses: Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin, Berthe Morisot)

today’s muse: Camille Pissarro, France (1830-1903)

There's a moment in every creative’s life when they have to choose between protecting what they've built and trusting their ability to keep building. Most people choose protection. They guard their work, their reputation, their hard-won techniques. They play it safe, accumulate achievements, hope nothing gets destroyed.

Camille Pissarro watched Prussian soldiers use his paintings as butcher paper—hundreds of works, nearly a decade of artistic development, literally destroyed. His response? "All the sorrow, all the bitterness, all the sadness, I forget them and ignore them in the joy of working." At forty-one, he simply started over. And created his greatest masterpieces.

This isn't a story about artistic success—it's about artistic resilience. About the revolutionary power of sustained attention, of trusting that the real art lives not in what you've made but in your capacity to keep seeing, keep responding, keep creating. In our age of digital hoarding and creative anxiety, Pissarro's story feels like an antidote: the courage to believe that as long as you can still observe the world with love, everything else can be rebuilt.

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born in 1830 on the Danish island of St. Thomas, where his Portuguese-Jewish father had built a prosperous hardware business far from European prejudices. The boy who would revolutionize French painting spent his childhood in a world of colonial contradictions—a place where Caribbean light danced differently than anything European art had ever tried to capture.

At twelve, his parents sent him to boarding school in France, expecting him to return and join the family business. But when young Camille came back to St. Thomas five years later, he carried sketchbooks instead of ledgers. His parents' plan had backfired. Instead of creating a dutiful merchant, the French education had awakened an artist. His father was horrified. The island's social expectations were clear: respectable merchants' sons didn't waste time with sketchbooks and paintbrushes.

Everything changed in 1849 when Fritz Melbye, a Danish painter, arrived on St. Thomas. Melbye had trained as a marine artist in Copenhagen under his brother Anton before making his way to the Caribbean. He saw something in twenty-year-old Pissarro's sketches that the boy's family couldn't—a natural eye for capturing light and atmosphere.

"Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing" would become Pissarro's philosophy, but it was already evident in his early works.

For nearly three years, the two painters worked together on St. Thomas, with Melbye teaching Pissarro the Danish plein air techniques he'd learned from Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg's school. They painted the harbor, the mountains, the daily life of the island, developing a body of work that would later be recognized as foundational to Impressionism's development.

In November 1852, the two men escaped to Venezuela together, Pissarro later saying he had "abandoned all I had and bolted to Caracas to get clear of the bondage of bourgeois life." For nearly two years, they worked side by side in their Caracas studio, exploring the mountains and painting South American life. Pissarro filled countless sketchbooks with street scenes, market life, and landscapes that would inform his democratic vision for decades to come.

The Venezuelan works taught him something fundamental about democratic observation. "It is only by drawing often, drawing everything, drawing incessantly, that one fine day you discover to your surprise that you have rendered something in its true character." In Caracas, he developed the visual habits that would define his entire career: patient observation, respect for ordinary subjects, and the belief that art should reflect authentic experience rather than idealized beauty.

In August 1854, Pissarro returned to St. Thomas, but this time as a changed man. He spent another crucial year on his home island, painting some of his most important Caribbean works during this period. These weren't nostalgic tourist views but mature statements by an artist who had found his voice.

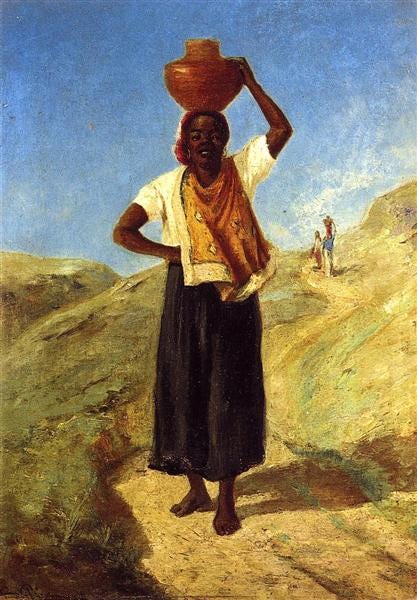

The woman carrying water embodied his emerging philosophy: the dignity of ordinary labor deserved artistic attention. A Creek in Saint Thomas (1856) demonstrated his growing mastery of tropical light, that particular Caribbean illumination that would forever inform his understanding of how light transforms landscape. "Everything is beautiful, all that matters is to be able to interpret"—and Pissarro was learning to interpret with unprecedented honesty.

The paintings from this final St. Thomas period show remarkable confidence. He was applying everything he'd learned in Venezuela to his childhood landscape, seeing the island with new eyes. Most of his St. Thomas paintings are dated 1856—the year he finally convinced his parents that his artistic determination was unshakeable.

When his parents finally realized that no amount of argument would change their son's commitment to painting, they agreed to let him pursue his dream. In 1855, twenty-five-year-old Pissarro sailed for Paris, carrying with him a Caribbean understanding of light and a democratic vision of subject matter that would revolutionize French painting.

Pissarro arrived in Paris during the Universal Exposition, where he was immediately drawn to the work of Camille Corot. This timing proved fortuitous—seeing contemporary art at the highest level just as he began his formal education.

The next five years were marked by poverty and persistence. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Suisse, a "free studio" where he met future Impressionists Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Armand Guillaumin. Through Monet, he also met Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. But these relationships took time to develop—first, Pissarro had to establish himself.

In these early Paris years, he painted scenes of the West Indies from memory while learning European techniques. He found crucial guidance from Anton Melbye, Fritz's brother, who was already established in the Paris art world. When Pissarro first showed work at the Paris Salon in 1859, he called himself "Pupil of A. Melbye," a title he continued to use until 1866.

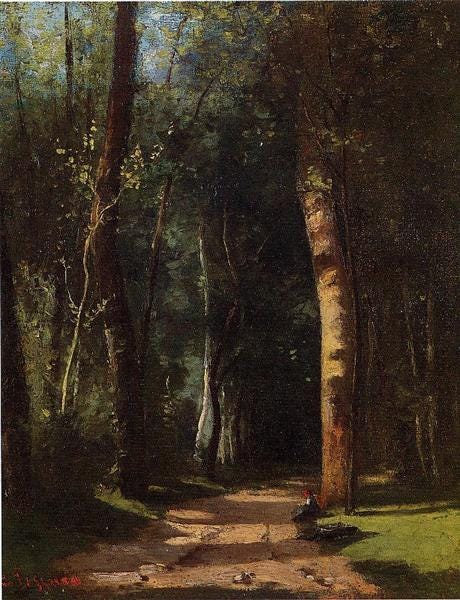

In the Woods (1859) shows him in transition, still learning European traditions but already questioning them. The forest breathes with an immediacy that academic landscapes rarely achieved—this is direct observation, not conventional composition. The painting marks his growing confidence in trusting his own eye over inherited formulas.

More importantly, Corot took him under informal mentorship, teaching him that painting could be meditation upon reality rather than improvement upon it. This lesson would prove foundational. Corot urged him to paint from nature, reinforcing the plein air habits Pissarro had learned in the Caribbean.

By 1860, Pissarro's parents had relocated from St. Thomas to Passy, a Paris suburb. It was during his frequent visits to the family home that he met Julie Vellay, a twenty-two-year-old woman from Grancy in Burgundy who had been hired as their maid. Julie was typical of the bonnes employed through agencies—an untrained, unsophisticated country girl with the high complexion of someone used to outdoor work.

Pissarro was immediately enchanted. They began meeting in secret on her days off, and within a year, Julie was pregnant. It is believed he said, "When you do a thing with your whole soul and everything that is noble within you, you always find your counterpart." This wasn't a casual artist-model affair—Pissarro truly loved Julie.

But his mother was more than scandalized; she was utterly ashamed that Camille could contemplate a liaison with a servant, let alone acknowledge a child by her. From that moment on, neither Julie nor their children existed in his mother's eyes. There would be no question of marriage until his parents died.

Their first child, Lucien, was born in 1863. Their second, Jeanne (nicknamed Minette), followed in 1865. Pissarro was learning to balance family responsibilities with artistic ambitions, finding subjects in both rural landscapes and domestic life.

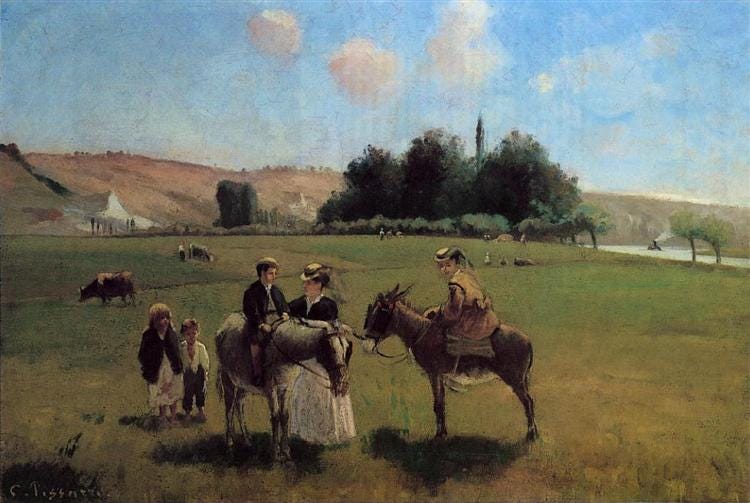

Donkey Ride at La Roche-Guyon (1864-1865) demonstrates his mastery of plein air techniques during this crucial period. The painting shows him discovering what would become the democratic heart of Impressionism—the artist as witness rather than interpreter, the canvas as space for authentic encounter rather than idealized representation.

By the mid-1860s, Pissarro had become a key figure in the emerging avant-garde. At the Café Guérbois, he joined younger artists like Monet and Renoir in heated discussions about art and politics. Though older than most, his gentle authority and fierce arguments about egalitarianism impressed everyone. He was seen as a father figure, the moral center of their rebellion against the Salon system.

In 1869, seeking cheaper living and better rural subjects, Pissarro moved his growing family to Louveciennes in the Seine valley. Renoir joined them that summer, while Monet worked nearby. This was a moment of great promise—the future Impressionists were developing their revolutionary techniques together, learning from each other's experiments with light and color.

The Franco-Prussian War in summer 1870 shattered this idyllic period. As Prussian troops advanced, Pissarro fled with Julie and their children to London, settling in Upper Norwood (now Crystal Palace). In London, he painted English landscapes while waiting for the war to end. More importantly, he met art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who bought two of his London paintings—the beginning of a crucial relationship.

On June 14, 1871, in Croydon, England, Camille and Julie finally married. With his parents still disapproving from afar, they had to make their commitment official quietly, away from family judgment.

When they returned to Louveciennes in June 1871, Pissarro discovered devastation that would have ended most artistic careers. Prussian soldiers had used his studio as a butcher shop, destroying hundreds of early paintings—nearly his entire artistic output from the 1860s. Imagine losing a decade of creative growth, all the experiments and breakthroughs and patient observations that had brought him to artistic maturity.

The financial blow was catastrophic, but the emotional devastation ran deeper. These weren't just paintings—they were proof of his artistic evolution, evidence that he had transformed from a colonial merchant's son into a serious artist. Gone. Used as meat-wrapping paper by occupying soldiers.

Most artists would have been paralyzed by such loss. Pissarro's response reveals something profound about the nature of creative resilience: "All the sorrow, all the bitterness, all the sadness, I forget them and ignore them in the joy of working." He understood something we often forget—that an artist's real strength doesn't lie in protecting what they've created, but in trusting their capacity to keep creating.

At forty-one, he didn't try to recreate what was lost. He simply began again, with the accumulated wisdom of his observations intact even if the physical evidence was gone. The way of seeing had survived; everything else could be rebuilt.

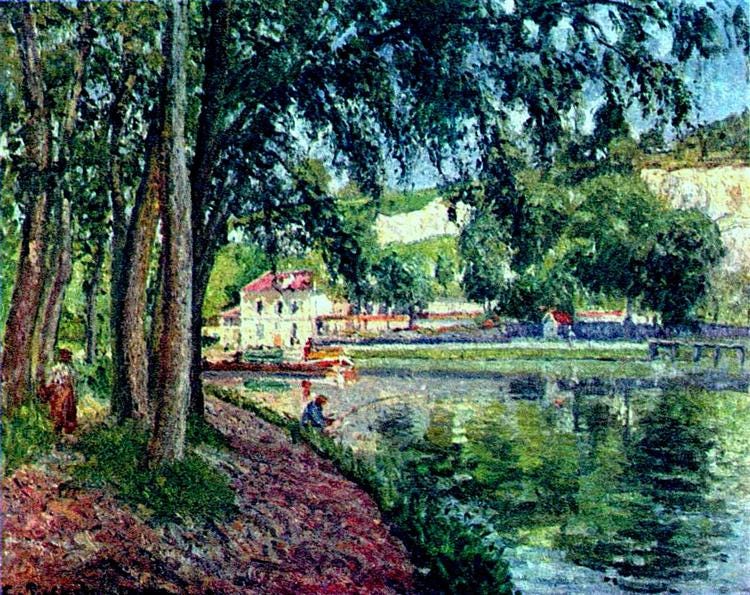

The early 1870s marked Pissarro's emergence as a mature artist. Moving to Pontoise in 1872, he began the most productive period of his career. Paul Durand-Ruel was now buying regularly, finally providing some financial stability for his growing family.

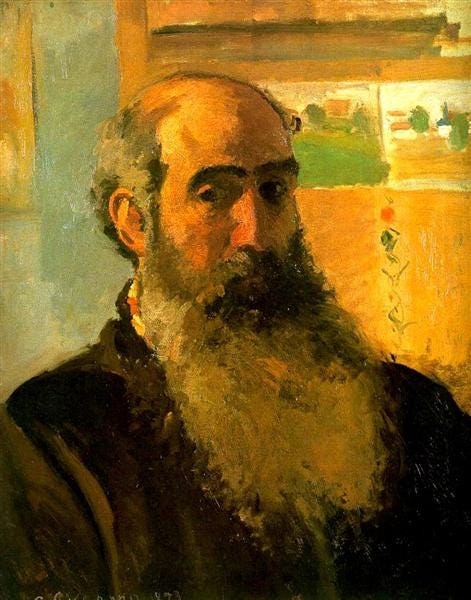

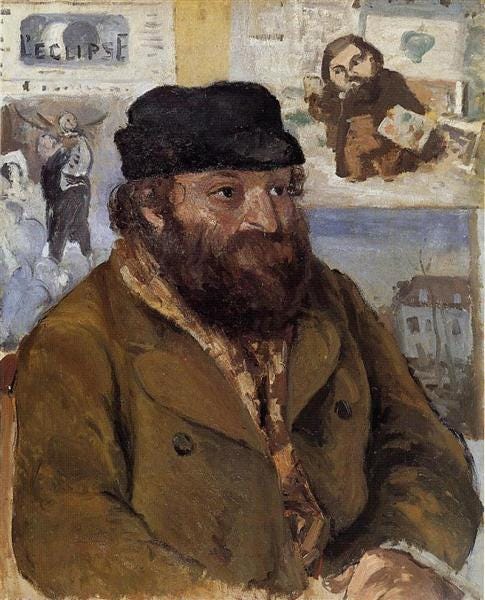

His Self Portrait (1873) reveals an artist who has survived catastrophe and found his place: bearded, serious, but with gentle eyes that speak of someone who has learned to see beauty in everyday rhythms despite profound loss. At forty-three, Pissarro had the weathered face of a man who had lived through war and poverty but maintained his fundamental optimism about human nature and artistic possibility.

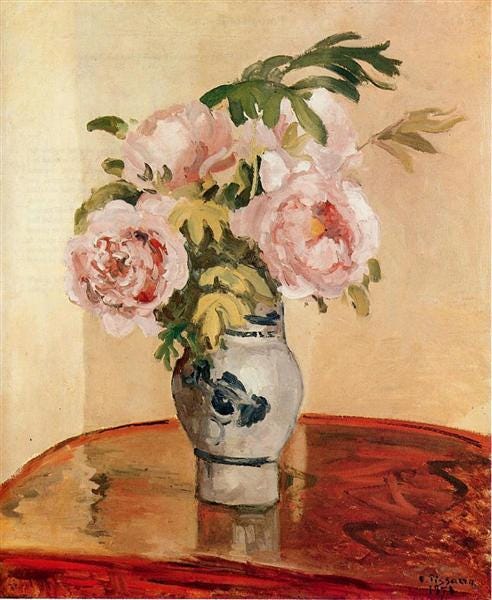

Pink Peonies (1873) captures this period of recovery—delicate, confident, showing mastery of Impressionist color theory. The flowers seem to glow with inner light, painted with broken brushstrokes that would become the movement's signature technique. It's a work of quiet joy, reflecting the domestic contentment Pissarro had found despite earlier struggles.

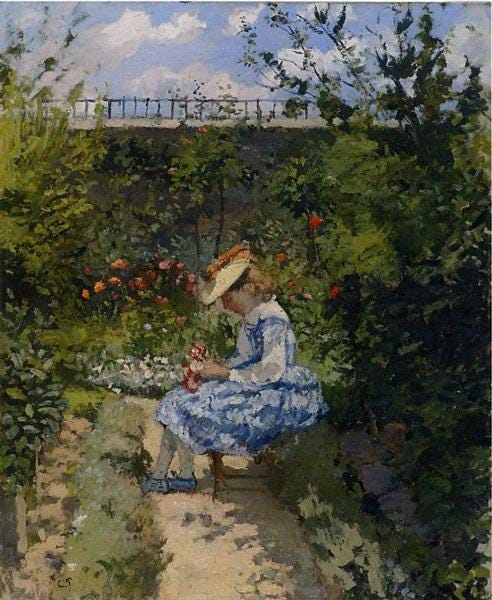

Jeanne in the Garden, Pontoise (Jeanne au Jardin) captures his beloved daughter in their family garden, a testament to the domestic happiness that sustained his art throughout all struggles. The painting embodies everything Pissarro believed about the intersection of love, observation, and artistic truth.

1874-1879: the impressionist years

In 1874, Pissarro became a founding member of the group that would be mockingly called "Impressionists." He was the only artist to participate in all eight of their exhibitions, serving as the movement's moral center and organizational backbone. While more famous colleagues like Monet focused primarily on their own work, Pissarro understood that sustained artistic revolution required collective action and mutual support.

Pissarro was the soul of the movement. The quiet radical. The kind of artist who changes the world slowly, by insisting on paying attention.

During these years, he worked closely with Paul Cézanne, who came to paint alongside him in Pontoise. Pissarro's generous mentorship helped Cézanne develop his distinctive style. Where others saw the awkward young painter from Provence as hopeless, Pissarro recognized genius struggling to find its voice. He didn't try to make Cézanne paint like an Impressionist—he helped Cézanne discover what it meant to paint like himself.