the art of contradiction: the metamorphosis of Odilon Redon

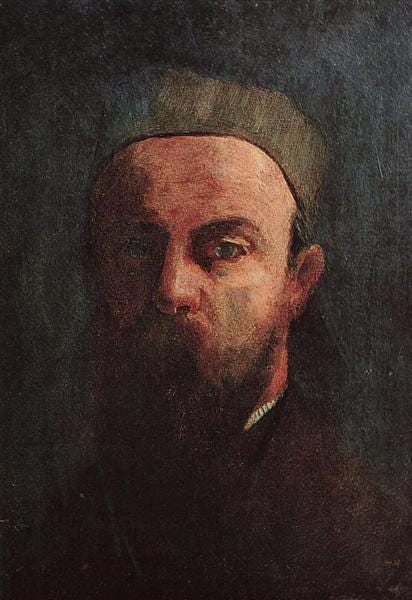

artist spotlight: Odilon Redon (France, 1840 - 1916)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together.

(Previous muses: Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro)

today’s muse: Odilon Redon, France (1840 - 1916)

There's a moment in every creative person's life when they have to choose: stay with what's working, or follow whatever is calling to them next, even if it makes no sense to anyone else. Most people choose safety. They find their lane and stay in it, build their reputation on consistency, become known for one thing and stick to it forever. They build on what came before, creating a logical progression that critics can trace and collectors can understand.

Odilon Redon did something far more radical: in his late fifties, after nearly three decades of creating some of the most haunting, mysterious drawings in art history—floating eyes, death masks, creatures from nightmares—he suddenly exploded into color. Not tentative color, not gradual color, but flowers that looked like they were made of pure joy, pastels that seemed to pulse with life force.

It was as if he had spent thirty years mining his psychological depths and finally struck gold. The same hands that had drawn monsters started painting paradise. The "Prince of Dreams" became the painter of impossible blooms.

This isn't a story about artistic evolution—it's about creative metamorphosis. About the courage to completely contradict your established reputation when your inner landscape shifts. In our niche-obsessed world where personal brands demand consistency, Redon's transformation feels like a quiet rebellion: proof that following your authentic creative instincts matters more than maintaining a coherent artistic identity.

The Solitary Dreamer (1840-1870)

Bertrand-Jean Redon—nicknamed Odilon after his mother's first name, Odile—was born in Bordeaux on April 20, 1840, to a family marked by fortune and complex circumstances. His father, Bertrand Redon, was French but had traveled to Louisiana as a young man, where he accumulated wealth—likely through landholding and colonial trade—and met Odilon’s mother, Marie Guérin, a French Creole woman.1 The couple returned to France before Odilon's birth, but their exotic background and unconventional history set the family apart from typical bourgeois society.

Young Odilon's childhood was profoundly shaped by isolation and health challenges. He was the second of five children in the Redon family—with an older brother Ernest (who became a musician), a sister Marie, and younger brothers Léo and Gaston (who would later become a noted architect). Due to poor health—documents suggest he suffered from epilepsy from around age four2—he was sent to live with an uncle at the family estate of Peyrelebade in the countryside, separated from his parents and siblings.

This solitary childhood, surrounded by the dramatic landscape of the Médoc region, became foundational to his artistic vision. The atmospheric qualities of this countryside—its subtle light and mysterious ambiance—would later influence the phantasmagorical worlds that appeared throughout his work. He spent countless hours alone, reading the dark romantic poetry of Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert, absorbing their fascination with the mysterious and fantastical

At ten, he won a drawing prize at school, showing early artistic promise. In 1855, his parents arranged for him to study with the watercolorist Stanislas Gorin, who had a profound influence on the budding artist. Gorin's first words to him were crucial: he "advised me that I was myself, and that I should never make a single mark with a pencil unless my feeling and my reason were in it." Gorin introduced him to the works of Eugène Delacroix and other Romantic masters, whose visionary approaches would deeply influence Redon's developing aesthetic.

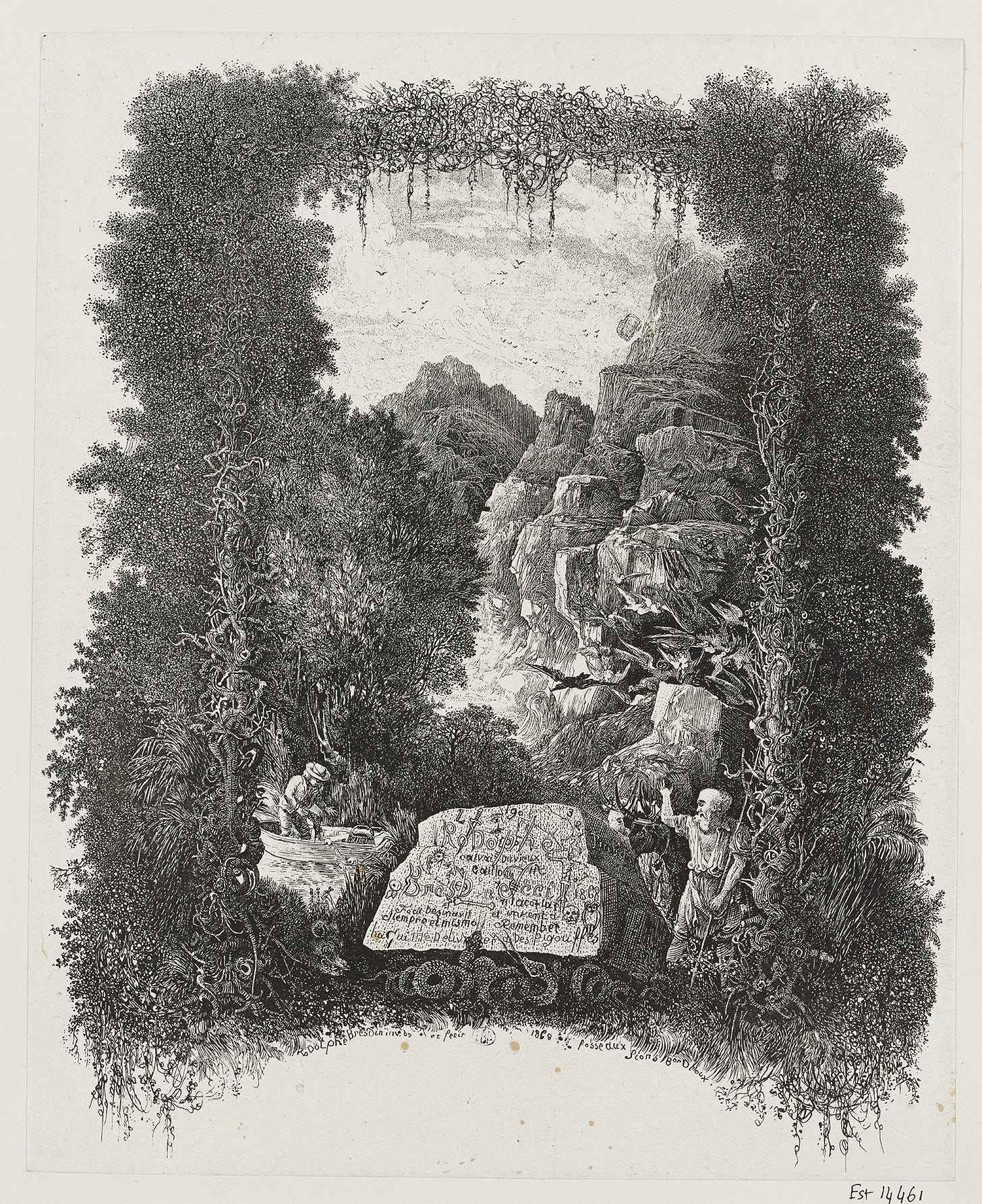

His father insisted he study architecture—practical career planning for a bourgeois son—but in 1857 Redon failed the entrance exams for architectural studies at the École des Beaux-Arts. This failure proved fortunate, steering him definitively toward art. In 1863, back in Bordeaux, he met Rodolphe Bresdin, the eccentric printmaker who would become his mentor in etching and lithography. Bresdin's visionary, mysterious works showed Redon that art could be a vehicle for exploring the unconscious and the fantastic.

During these formative years, Redon also befriended the botanist Armand Clavaud, who opened his mind to natural sciences, evolutionary theory, and Eastern philosophy. Clavaud introduced him to the works of Darwin and Lamarck on evolution, Pasteur's research on microbes, and—crucially—Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. This early exposure to Eastern spirituality would profoundly influence his later work, when figures of Buddha would increasingly appear in his paintings.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 marked a definitive turning point. Drafted into military service, Redon experienced the trauma of war and France's humiliating defeat. The experience deepened his natural melancholy and pushed him further toward symbolic rather than literal representation.

Interesting note on Odilon's brother Gaston: Gaston Redon won the Prix de Rome for architecture in 1883, spent three years at Villa Medici, and after his return to Paris was made the official architect of the Louvre. He was responsible for major work including the rebuilding and expansion of the Pavillon de Marsan between 1900 and 1905 to accommodate the Museum of Decorative Arts.

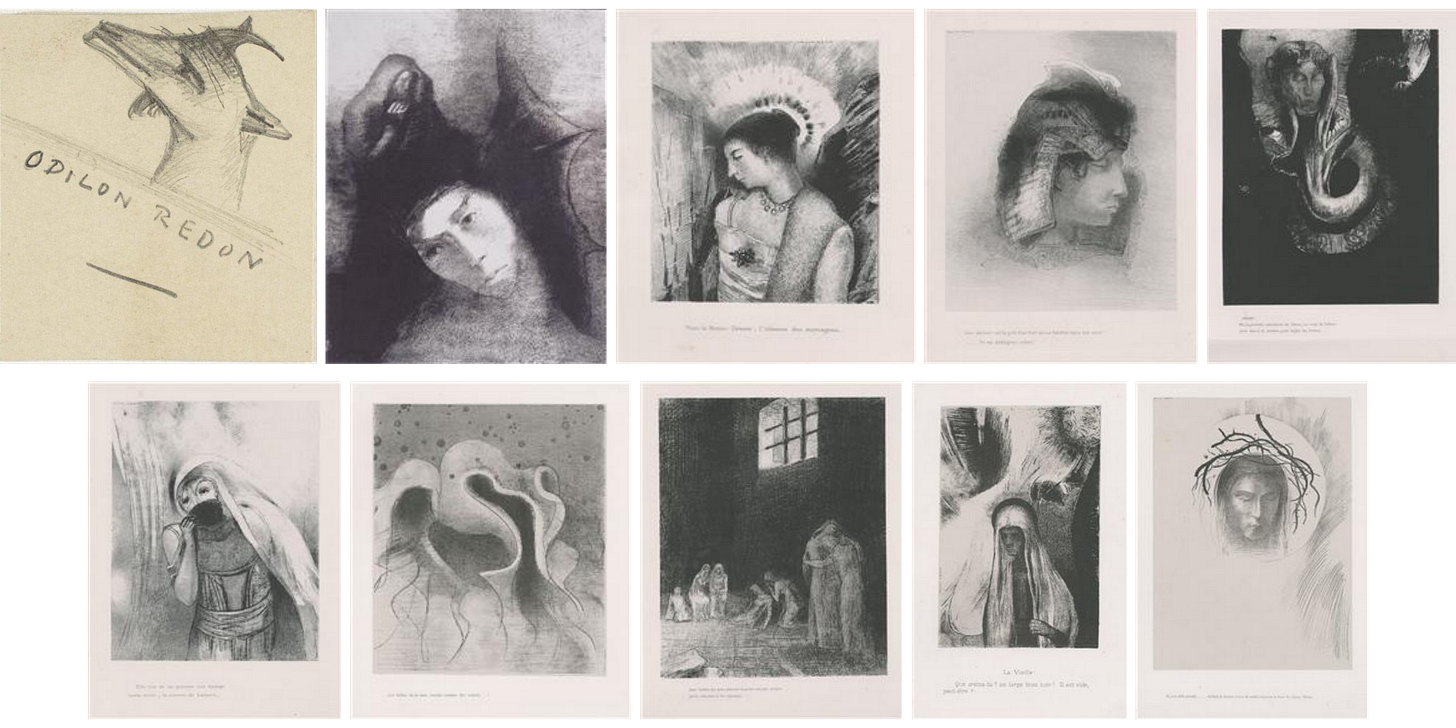

The Prince of Dreams (1870-1890)

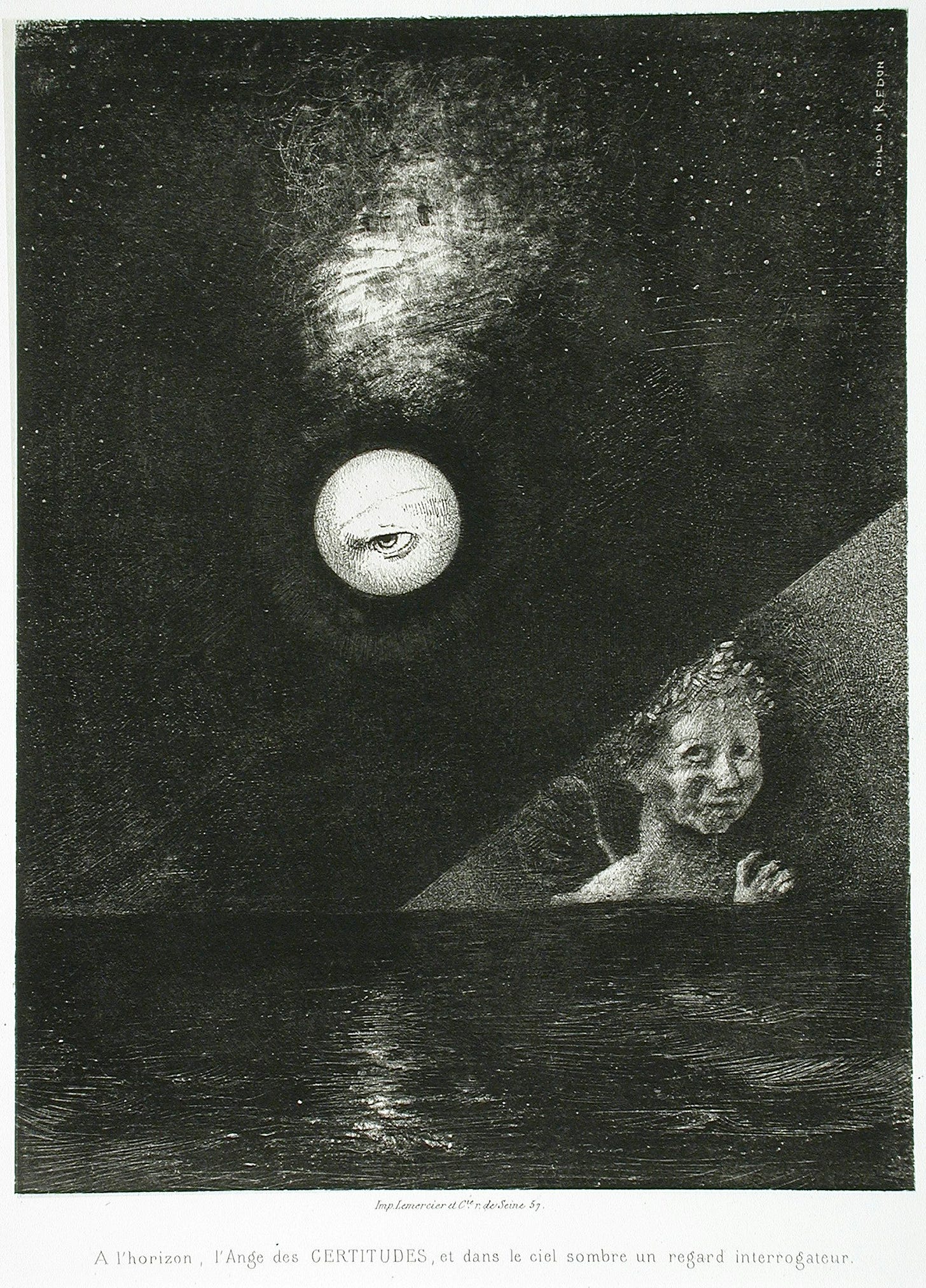

Returning to Paris after the war, Redon began working on what he called his "noirs"—monochromatic charcoal drawings and lithographs that exploited the medium's inherently rich blackness. “Black is the most essential color. Nothing can prostitute it,” he declared.3 For him, black became the ideal medium for expressing his imagination and the mysterious contents of the unconscious mind.

Critics began calling him the "Prince of Dreams"—sometimes mockingly, sometimes with genuine admiration—because his images seemed to emerge from the unconscious mind rather than the visible world. Unlike the Impressionists who were painting what they saw in daylight, Redon was painting what he saw when he closed his eyes. "My drawings inspire, and are not to be defined. They place us, as does music, in the ambiguous realm of the undetermined."

In 1872, Redon began frequenting the literary and musical salon of Madame de Rayssac, where he met the composer Ernest Chausson and formed what would become a lifelong friendship. Chausson, fifteen years younger than Redon, was a talented violinist, and the two men regularly played chamber music together—Chausson on piano, Redon on violin.

In 1876, Redon met the poet and art critic Stéphane Mallarmé, beginning another crucial friendship that would define his intellectual life. Mallarmé was the leader of the Symbolist movement in literature, and his Tuesday evening salons at his Paris apartment became the gathering place for the most innovative artists and writers of the time. Regular attendees included Paul Verlaine, André Gide, Oscar Wilde, painters like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Auguste Renoir, and the sculptor Auguste Rodin.

For Redon, these gatherings were transformative. Mallarmé's aesthetic theories—his belief that art should "suggest" rather than describe, that poetry should evoke "a state of the soul" through mystery and symbol—aligned perfectly with Redon's visual approach. This shared interest in the mysterious and symbolic would influence Redon's work throughout the 1880s, including his 1882 lithographic series 'To Edgar Allan Poe,' which drew from the American writer's dark, visionary imagery that both men admired.

His first major recognition came in 1878 with Guardian Spirit of the Waters, followed by his first lithographic series, In the Dream (1879). These works featured floating eyeballs, mysterious flowers with human faces, mythological creatures that belonged to no earthly taxonomy. The images were beautiful and disturbing in equal measure, like beautiful nightmares that you can't quite shake upon waking.

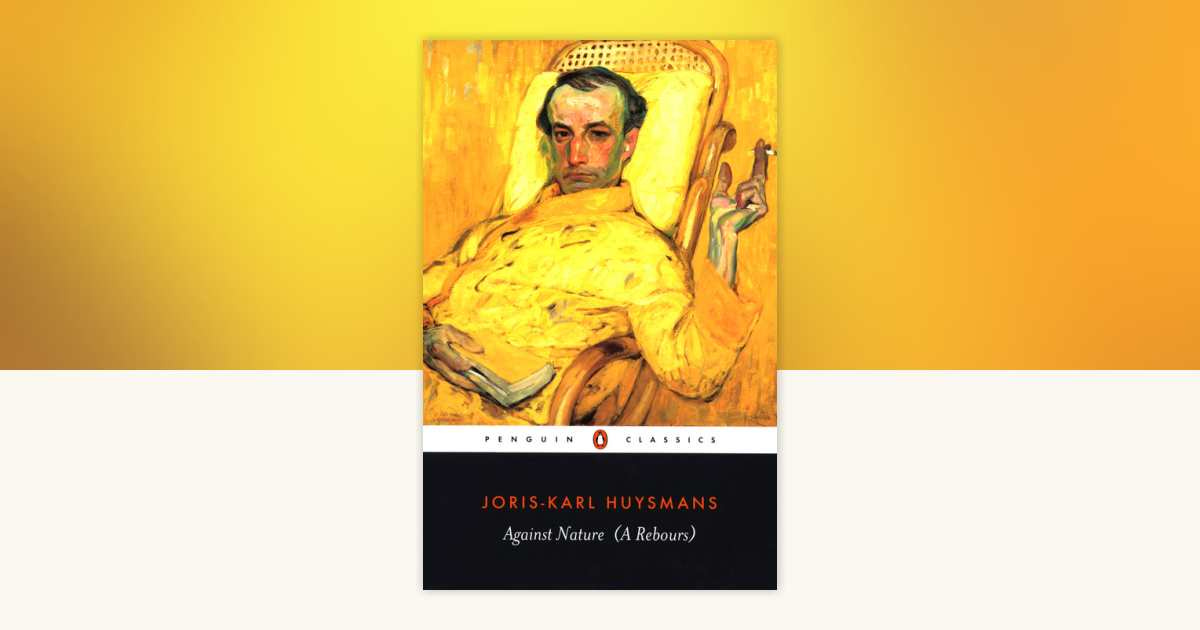

During this period, Redon worked primarily on lithographs, creating several portfolios conceived as accompaniments to literary works. To Edgar Poe appeared in 1882, and The Temptation of Saint Anthony, inspired by Flaubert's novel, in 1896. His work gained wider recognition after being featured prominently in Joris-Karl Huysmans's decadent novel À rebours (Against Nature) in 1884, where the protagonist's art collection includes several of Redon's mysterious lithographs.

I think about Redon during this period when I'm in my own creative dark phases, when everything I make feels heavy or difficult or too weird for public consumption. His work reminds me that sometimes you have to go deep into whatever psychological territory is calling to you, even if—especially if—it makes other people uncomfortable. The darkness isn't a detour from your real work; it might be preparation for something you can't even imagine yet.

Love and Transformation (1880-1895)

In 1880, at age forty, Redon married Camille Falte, a young Creole woman from Bourbon Island (now Réunion) whom he had met in Madame de Rayssac's salon. Of their marriage, he said: "I believe the yes that I uttered on the day of our union was the expression of the most complete and unadulterated certainty I ever experienced. A certainty more complete even than my vocation."

Their honeymoon in Brittany marked the beginning of a crucial shift—it was there that Redon made his first serious exploration of pastels, moving away from the charcoal and lithographic works that had dominated his career since the Franco-Prussian War. Camille proved to be not just a beloved partner but a practical support, handling interactions with dealers and the press while Redon focused on his art.