the man who freed color: the life, influences, & artistic evolution of Henri Matisse

artist spotlight: Henri Matisse, France (1869-1954)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together.

previous muses:

Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Odilon Redon

There are artists who capture specific moments of our aesthetic understanding—masters whose work we admire within certain periods, appreciating their revolutionary contributions while perhaps finding other phases less compelling. And then there are those rare souls whose creative journey feels so authentic, so fearlessly committed to the pursuit of beauty and truth, that every creative execution across six decades feels like a personal revelation.

Henri Matisse is, for me, one of those extraordinary beings.

It's unusual to love every era of an artist's work with equal admiration. Most painters have their watershed moments followed by periods of decline, experimentation that doesn't quite land, or commercial compromises that dilute their vision. But with Matisse, I find myself being equally moved by his careful 1896 landscapes and his revolutionary 1952 cut-outs, by his academic copies and his most radical innovations.

Perhaps this speaks to something fundamental about Matisse's character—a relentless integrity that refused to separate technical mastery from emotional honesty, tradition from innovation, beauty from meaning. In an art world often driven by the need to shock or to signal intellectual sophistication, Matisse pursued something more elusive and, I believe, more essential: the direct transmission of joy through color and form.

This is why I'm particularly excited to feature him as today’s wild bare muse. In a cultural moment that often seems to reward cynicism over wonder, studying Matisse feels like a radical act—an insistence that beauty matters, that the visual world can be a source of profound meaning, and that an artist's highest calling might simply be to make the world more alive to itself.

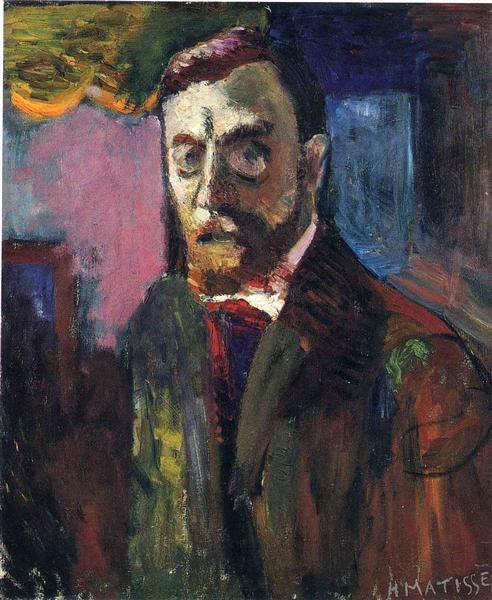

In the quiet rooms of recovery, sometimes destiny whispers its truest calling. Henri-Émile-Benoît Matisse, born on New Year's Eve 1869 in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, a small industrial town in northern France, discovered his life's purpose not in a moment of grand revelation, but during a humble period of convalescence following an attack of appendicitis. His mother, recognizing her son's restlessness during his recovery from appendicitis in 1889, brought him a box of paints.

As Matisse later described this pivotal moment, he found himself in what felt like paradise—a place of complete freedom and tranquility, vastly different from the anxiety and boredom that had characterized his previous pursuits. At twenty years old, this future revolutionary of modern art was still a law clerk, dutifully following the path laid out by his father, Émile-Hippolyte-Henri Matisse, a grain and hardware merchant.

The tension between bourgeois expectation and artistic calling would define Matisse's early years. His family embodied the practical, industrious spirit of northern France—his parents owned a flower business, a fact that perhaps planted the earliest seeds of his lifelong obsession with color and natural beauty. Yet there was something in young Henri that resisted the comfortable predictability of commerce, something that yearned for expression beyond the ledger books of his legal apprenticeship.

1891-1898

When Matisse finally abandoned law in 1891 to pursue art, he chose the most conventional path possible. In order to prepare himself for the entrance exam at the official École des Beaux-Arts, Matisse enrolled in the privately run Académie Julian, where the master was the strictly academic William-Adolphe Bouguereau. This choice seems almost comical in retrospect—the future leader of Fauvism studying under one of the most conservative painters of the 19th century, known for his sugar-sweet mythological scenes and polished technique.

But the pivotal moment came in 1892 when Matisse left the Académie Julian for evening classes at the École des Arts Décoratifs and for the atelier of the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau at the École des Beaux-Arts, without being required to take the entrance exam. This exception was crucial—Matisse had been denied admission to the École des Beaux-Arts, but Moreau saw him drawing in the public courtyard of the school and invited him to join his class, exempting him from the entrance examination.

Gustave Moreau was no ordinary professor. According to Matisse's later recollections, Moreau possessed a rare quality—he viewed the mind of a young student as something that needed to develop continuously throughout life, rather than simply pushing pupils through academic examinations. Here was a teacher who understood that true artistic education was not about replication but revelation.

Moreau distinguished himself from his colleagues by wanting to know each of his pupils personally. Having spent considerable time studying the masters himself, he encouraged his pupils to visit the Louvre. Matisse would later describe this as an almost revolutionary approach for the time—making students go to the museum rather than simply copying plaster casts. Under Moreau's guidance, Matisse copied somber still lifes by Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, dynamic compositions by Eugene Delacroix, fine lines by Jean-Dominique Ingres, and balanced landscapes by Nicolas Poussin.

But perhaps most importantly, Moreau seemed to recognize something in Matisse that other teachers had missed—a temperament that would transform rather than merely absorb these classical influences. By 1896, when Matisse painted Maisons À Kervilahouen, Belle Ile, we can see this transformation already taking root. Far from the dutiful academic study one might expect, this Breton landscape pulses with an energy that suggests Moreau's lessons had awakened something profound. The brushwork carries an almost fevered urgency, those coral pinks bleeding into forest greens, that electric turquoise sky vibrating against white cottage walls. Here is visual evidence of a student who understood that studying the masters meant learning to see, not simply to copy—that the true lesson of Chardin's subtlety or Delacroix's dynamism lay not in replicating their surfaces but in discovering how they had transformed their own inner vision into paint.

This painting reveals the deeper wisdom of Moreau's pedagogy: he wasn't teaching technique so much as permission—permission to trust one's instincts, to let emotion guide observation, to understand that tradition exists not as limitation but as foundation for personal expression.

But what I find most profound here is how this painting exposes the myth of linear artistic development. We want to believe that revolutionaries begin conservatively and gradually grow bold, but Matisse's journey suggests something more complex: perhaps some artists are born with a fundamental inability to see the world as others do, and their education becomes less about learning rules than about finding the courage to trust their own vision. Even in 1896, seven years before his Fauve explosion, Matisse was already asking the question that would define his career: what if color could bypass rational representation and speak directly to emotion? In these deceptively modest Breton fields, we witness not an artist learning to rebel, but a rebel learning to trust himself.

The Foundation of Draftsmanship

Even as Matisse would later become renowned for his revolutionary use of color, his commitment to drawing remained unwavering throughout his career. This period under Moreau established drawing as the bedrock of his artistic practice—a discipline he would maintain with almost religious devotion for the rest of his life. His line work, which would culminate decades later in masterful series like Themes and Variations, began here in the careful study of Renaissance masters.

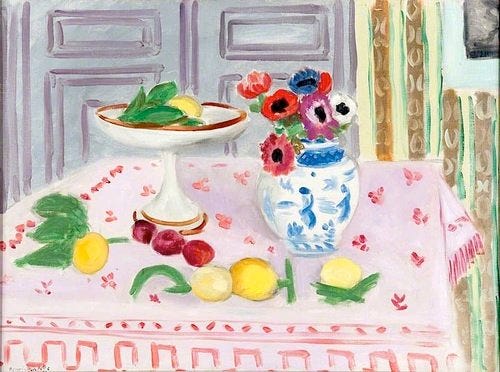

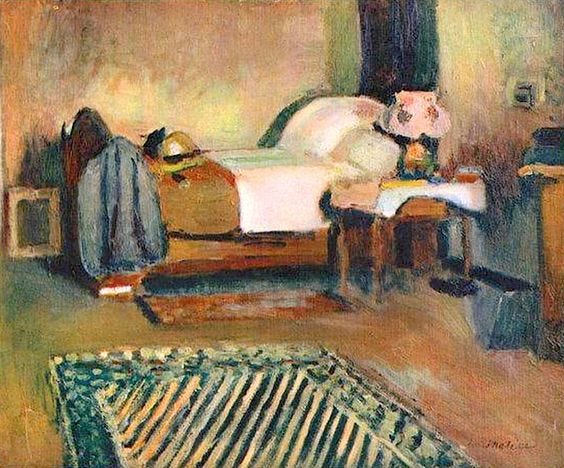

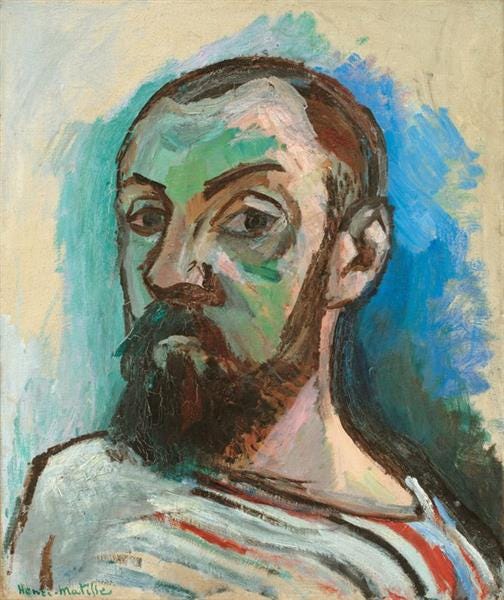

This systematic study of the masters was not mere copying—it was absorption, transformation, a kind of artistic DNA sequencing that would later allow Matisse to synthesize centuries of artistic tradition into something entirely new. My Room in Ajaccio (1898) and his Self-Portrait (1900) show this deepening understanding of form and structure, though still rendered in relatively traditional colors and techniques.

1898-1904

In 1898, Matisse married Amélie Parayre, a young woman from Toulouse, marking both personal and artistic transition. This union would prove foundational to his career—Amélie provided not just emotional support but practical stability, managing their household and finances while Henri devoted himself to his art. Marriage brought stability but also responsibility—the need to sell work, to build a reputation, to navigate the complex world of Parisian art politics.

Amélie's support was particularly crucial during their early years of financial struggle. She believed in her husband's vision even when the art world remained skeptical, and her faith sustained him through the difficult period when his work was dismissed as chaotic or incompetent. During the next two years he undertook expeditions to Brittany, met the veteran Impressionist Camille Pissarro, and discovered the series of Impressionist masterpieces in Gustave Caillebotte's contemporary art collection, which had just been donated—amid protests from conservatives—to the French nation.

These encounters with Impressionism marked a crucial shift. Matisse's colors became, for a while, lighter in hue and at the same time more intense. We see this evolution clearly in works like Pierre with Wooden Horse (1904), where the child's portrait reveals a new confidence with color, a willingness to let emotion guide the brush rather than strict observation.

The Cézanne Obsession

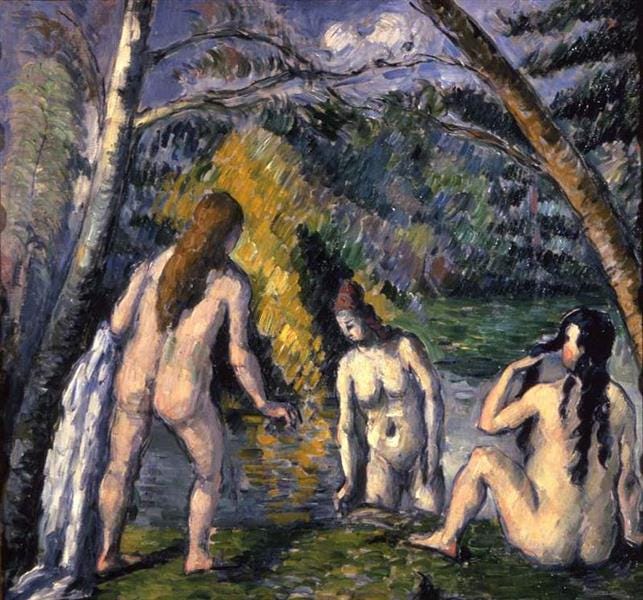

The most profound influence of this period was Paul Cézanne. In 1899, Matisse purchased Cézanne's Three Bathers, a painting he would contemplate every morning for years. According to his biographer Hillary Spurling, Matisse seemed to absorb Cézanne into his very essence at such a fundamental level that the specific connections become difficult to trace—like water seeping into earth, transforming everything it touches.

This daily communion with Cézanne's work was transformative. Cézanne showed Matisse that painting could be both respectful of nature and radically interpretive, that structure and spontaneity were not opposites but partners in the dance of creation. The influence appears in the architectural quality of Matisse's compositions from this period, in his growing confidence with color as a structural rather than merely descriptive element.

In 1904, Matisse also read Paul Signac's essay on Neo-Impressionism, which advocated for a more systematic approach to color. This theoretical foundation, combined with his visceral response to Cézanne, created the intellectual and emotional framework for his coming revolution.

1904-1907

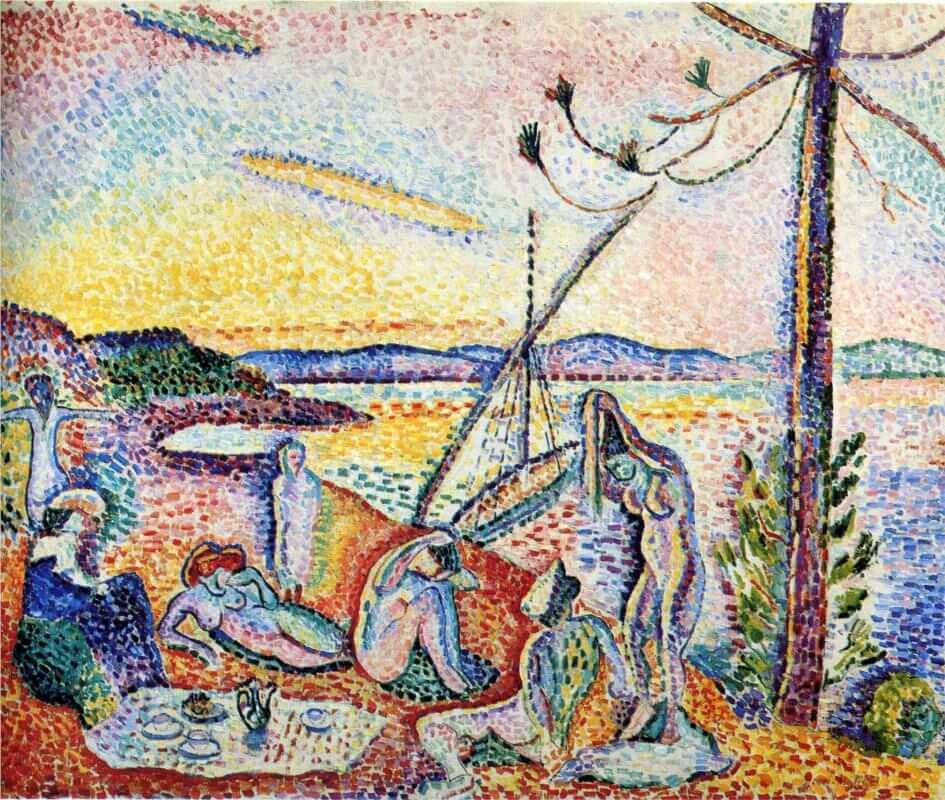

The summer of 1904 marked a watershed moment. While visiting his artist friend Paul Signac in Saint-Tropez, a small fishing village in Provence, Matisse discovered the bright light of southern France, which contributed to a change to a much brighter palette. He also was exposed, through Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, living in nearby Lavandou, to a pointillist technique of small color dots (points) in complementary colors, perfected in the 1880s by Georges Seurat.

This exposure to Neo-Impressionism was like a chemical catalyst. In that year, he painted the most important of his works in the neo-Impressionist style, Luxe, Calme et Volupté. But Matisse was not content to remain within the bounds of any single technique. He was searching for something more direct, more emotionally immediate.

The crucial summer came in 1905 when he travelled southwards again to work with André Derain. Henri Matisse and André Derain, working together in the small fishing port of Collioure on the Mediterranean coast, introduced unnaturalistic color and vivid brushstrokes into their paintings.

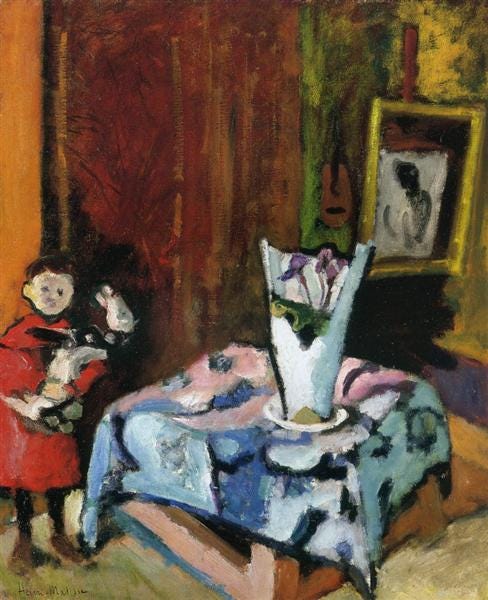

In the blazing light of the Mediterranean, something clicked. Color began to liberate itself from its descriptive function, becoming instead a language of pure emotion. Flowers (1906) shows this transformation in full bloom—colors that pulse with their own energy, that refuse to be bound by the logic of natural observation.

The Salon d'Automne Scandal

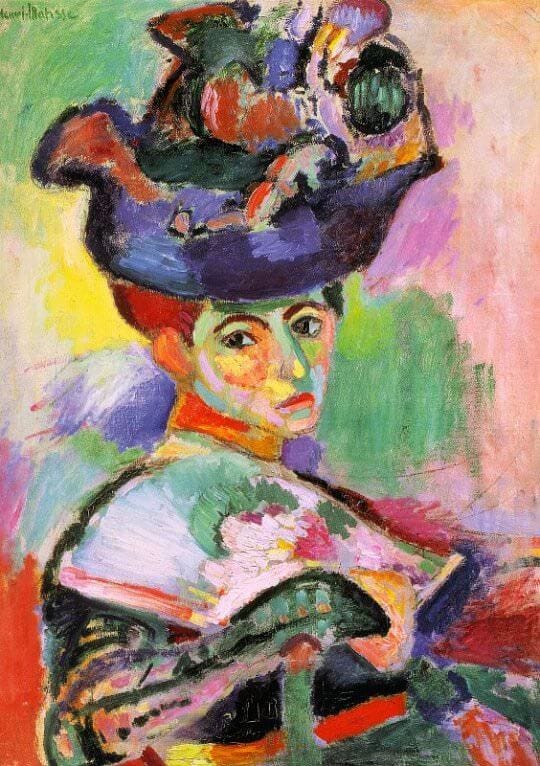

When Matisse and his fellow painters exhibited at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in Paris, critic Louis Vauxcelles coined the term "Fauves" (wild beasts) to describe their radical use of color. The exhibition garnered harsh criticism—one critic famously declared that a pot of paint had been flung in the face of the public—but also attracted crucial support.

The moment that changed everything came when Gertrude and Leo Stein purchased Matisse's controversial "Woman with a Hat"—the painting that had been singled out for particular condemnation. This purchase not only provided financial relief but, more importantly, validated Matisse's belief that his artistic vision had merit. Here was confirmation from collectors who understood they were witnessing something revolutionary.

Enter Picasso: A Creative Dialectic

In 1905, a meeting occurred that would reshape the trajectory of modern art. At Gertrude Stein's salon at 27 rue de Fleurus, Henri Matisse met Pablo Picasso—a encounter that sparked one of the most significant creative dialogues in art history.

The two men could hardly have been more different. Matisse, twelve years older, embodied the careful, methodical approach of a northern European craftsman. His revolutionary use of color was balanced by an underlying respect for harmony and beauty. Picasso, the young Spanish prodigy, possessed a restless intelligence that seemed to devour and transform every artistic tradition it encountered.

Their friendship-rivalry became a driving force for both artists. Each pushed the other toward greater innovations, though they pursued fundamentally different paths. Where Matisse sought to construct form through color relationships, Picasso deconstructed objects into geometric planes. Where Matisse aimed to create art that would be, in his words, like a comfortable armchair for the soul, Picasso often aimed to disturb and challenge.

Pablo Picasso himself acknowledged this dynamic when he observed that, all things considered, there was only Matisse. This wasn't mere politeness—it was recognition of a creative equal whose approach, while completely different from his own, achieved comparable revolutionary impact. Their Saturday evening encounters at the Steins' salon became legendary, two masters testing ideas against each other, each secretly learning from the other's innovations while publicly maintaining their distinct artistic territories.

This relationship would endure for decades, each artist's career serving as a counterpoint to the other's. When Matisse retreated to Nice and seemed to embrace a more traditional approach, Picasso continued his radical experiments with Cubism. When Picasso later explored more classical themes, Matisse was pioneering his revolutionary cut-out technique. Their parallel yet divergent paths illuminate the multiple directions modern art could have taken—and did take—in the twentieth century.