The Architecture of Loneliness & The Legacy of Edward Hopper

artist spotlight: Edward Hopper, United States (1882-1967)

The wild bare muses series is an archive of paintings I can’t stop looking at and artists I wish I could talk to. Short(ish) visual essays on art history, beauty, influence, and whatever else comes through the frame, typically focused on a single artist at a time. My hope is that it feels as if we’re wandering through a gallery of the artist’s life together.

previous muses:

Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Paul Gauguin, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Henri Matisse

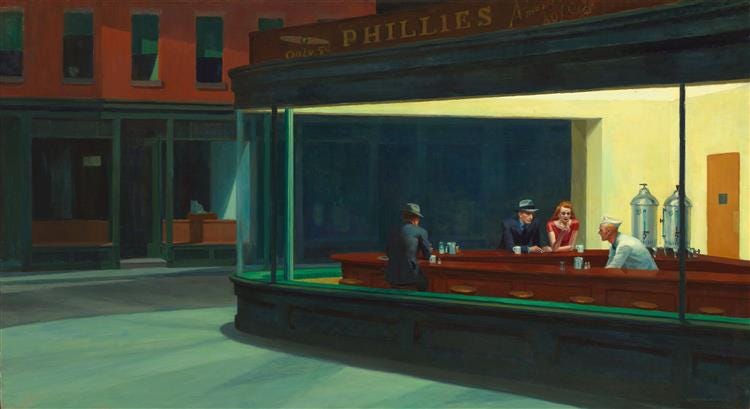

When most people hear “Edward Hopper,” they immediately picture Nighthawks. That fluorescent-lit diner at night, a few solitary figures who seem cut off from the world and from each other. It’s been reproduced so many times it’s practically cultural wallpaper. The painting has become visual shorthand for American loneliness, referenced in everything from films to memes until it’s lost almost all meaning.

But here’s the thing many people miss. Nighthawks isn’t actually about four lonely people who can’t connect with each other. If you look at the painting itself, there’s a couple leaning toward one another. Their body language suggests intimacy, maybe even affection. There’s a solitary customer sitting alone with his thoughts, and a server doing his job. So where does all that famous loneliness come from?

It comes from the space itself. The loneliness isn’t interpersonal. It’s architectural. The bright diner creates an island of wakefulness in a city that’s gone dark and silent. The huge plate glass windows separate everyone inside from the emptiness beyond. What Hopper captured is that peculiar suspension you feel at three in the morning when you’re awake and the rest of the world has shut down. The couple might be connecting just fine, but they’re still trapped in that eerie bubble of late-night consciousness, that feeling of existing outside normal time.

This distinction matters because once you understand that Hopper wasn’t painting people who can’t reach each other but rather the psychological architecture that modern life builds around us, his entire body of work starts to make a different kind of sense.

What makes Hopper one of my personal favorite artists is how his work operates on a frequency that takes time to perceive. Nothing about it is flashy or immediately conceptual. It’s a slow-burn. A single painting might feel quiet, even mundane. A woman at a window. A couple on a porch. Passengers on a train. But when you zoom out across the decades, the throughlines become sharp and incredibly resonant. You realize he was attempting something nobody else was doing. He was framing the silence between stories, mapping the psychological architecture of modern American life before anyone had language for it.

Edward Hopper isn’t a painter of moments so much as the absence of them. He didn’t document history, and he didn’t exaggerate it. He painted the spaces in between. The pauses. The silences. The stillness before something happens or the quiet ache after it passes. You could argue he was one of the most honest American painters to ever live, precisely because he didn’t try to mythologize anything. He didn’t paint the dream. He painted the cost of it.

Hopper was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, a small shipbuilding town on the Hudson River about twenty-five miles north of Manhattan. He came of age during the tail end of the Gilded Age, when American optimism was often theatrical and cities were expanding upward and outward at a dizzying pace. Advertising, mass entertainment, and urban spectacle were starting to define the national consciousness. Everything was about speed and flash and noise.

Hopper wanted absolutely no part of it.

From the beginning, there was something deeply reserved about him. He grew to be six foot five, towering over everyone around him, yet somehow he managed to take up no space at all. People who knew him later in life would describe his almost painful reserve, the way he could sit through an entire dinner party without speaking. His silence was so complete it became its own kind of presence. He had a genuine aversion to anything he considered false or performative, which in early twentieth-century America meant he had an aversion to quite a lot.

His parents were middle-class and respectable, devoutly Baptist, the kind of people who believed in hard work and quiet dignity. They encouraged his early interest in drawing but made it clear that art would be a hobby, not a profession. The real world required practical skills.

By eighteen, Hopper had enrolled at the New York School of Art to study commercial illustration. That was the practical path his parents wanted. But while he was there, he studied under Robert Henri, a realist painter who was known for encouraging students to capture the grit and soul of modern life. Henri’s other students took this directive literally. They found vitality in city crowds, energy in urban chaos. The Ashcan School was being born right there in those classrooms, committed to depicting the raw, pulsing life of the city.

But Hopper absorbed Henri’s teaching and took it somewhere stranger and quieter. He saw life around him, sure, but what he saw was the pause between moments, the stillness that exists even in crowded spaces. Where his classmates painted movement and noise, Hopper painted the breath between words, the moment when time seems to stop and you become suddenly, acutely aware of your own consciousness.

You can see this sensibility already formed in Model in Towel, Sitting on Box from 1902. The model isn’t trying to be provocative or idealized. She’s just there, wrapped in fabric and withdrawal, caught in a moment of private existence. This is what distinguished Hopper even at twenty. He understood that the most revealing moments are the ones we’re not performing, when we believe no one is watching and our interior life rises to the surface.

Between 1906 and 1910, Hopper made three trips to Europe. He absorbed the influence of Degas and Rembrandt, and he was particularly drawn to the clarity and compositional rigor of Vermeer. He studied the Old Masters, learned from their use of light and space. But Hopper wasn’t interested in Europe’s romance or its bohemian fantasies. When he came back to America, it wasn’t to chase artistic movements or join avant-garde circles. He returned to document the silent strangeness of American life.

“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world,” Hopper once said. And what a vision it was. He didn’t invent a new style. He perfected a mood. A Hopper painting doesn’t ask you to interpret it. It asks you to sit with it. To inhabit the light. To feel the air. To notice what isn’t there.

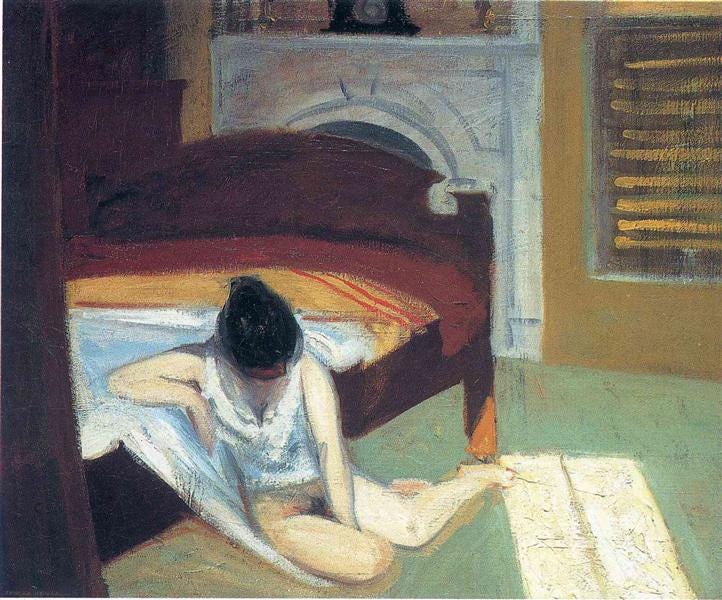

By 1909, when he painted Summer Interior, Hopper had refined his vision into something sophisticated and strange. A woman is sprawled on a floor in harsh light. The scene carries a weight of psychological intensity, but it’s not drama exactly. It’s more like the raw presence of someone completely alone with themselves. The light doesn’t romanticize anything. It just reveals. It makes visible the texture of solitude, the particular quality of consciousness when it’s not directed toward anything, just existing in space and time.

His paintings read like antidotes to the spectacle of American progress. Each one is a refusal to perform, a commitment to showing what was actually there rather than what was supposed to be there.

Hopper was what you’d call a late bloomer. He sold his first painting, Sailing, at the 1913 Armory Show when he was thirty-one. But widespread recognition wouldn’t come for another decade after that. In the meantime, he endured a long, brutal sales drought. To support himself, he took commercial illustration jobs that he absolutely detested. He was designing advertisements and drawing covers for trade magazines, creating images for a world obsessed with speed and spectacle when all he wanted to paint was stillness and silence.

He went years without selling a single painting. And yet he kept painting anyway.

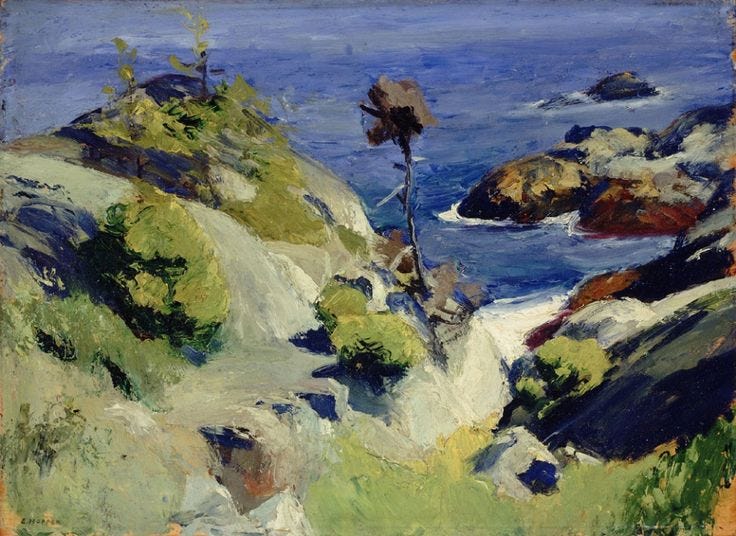

Between 1916 and 1919, Hopper escaped to Monhegan Island in Maine, a rocky outcrop where the Atlantic crashes against granite cliffs. The paintings he made there, like Bluff and Monhegan Landscape, show him investigating the same psychological territory even in unpeopled scenes. These aren’t celebrations of wilderness or sublime nature. They’re meditations on presence itself. What it feels like to stand in a place and simply observe, to let the world exist without imposing narrative or meaning on it. The way emptiness can feel simultaneously peaceful and unsettling.

He was in his mid-thirties, watching contemporaries find success while his own career remained stalled. But these paintings suggest something crucial about Hopper’s temperament: he wasn’t interested in success as validation. He was interested in seeing clearly, in finding visual form for experiences that had no existing language.

When he painted New York Restaurant in 1922, you can see his vision really maturing. Notice what he chooses to frame. Not the bustle of dining or the performance of sociability, but the quiet between interactions. The figures occupy the same space but exist in separate psychological territories. This isn’t about people failing to connect. It’s about the peculiar quality of modern public space, where proximity doesn’t necessarily create intimacy, where we can be surrounded by others and still remain entirely alone with our thoughts.

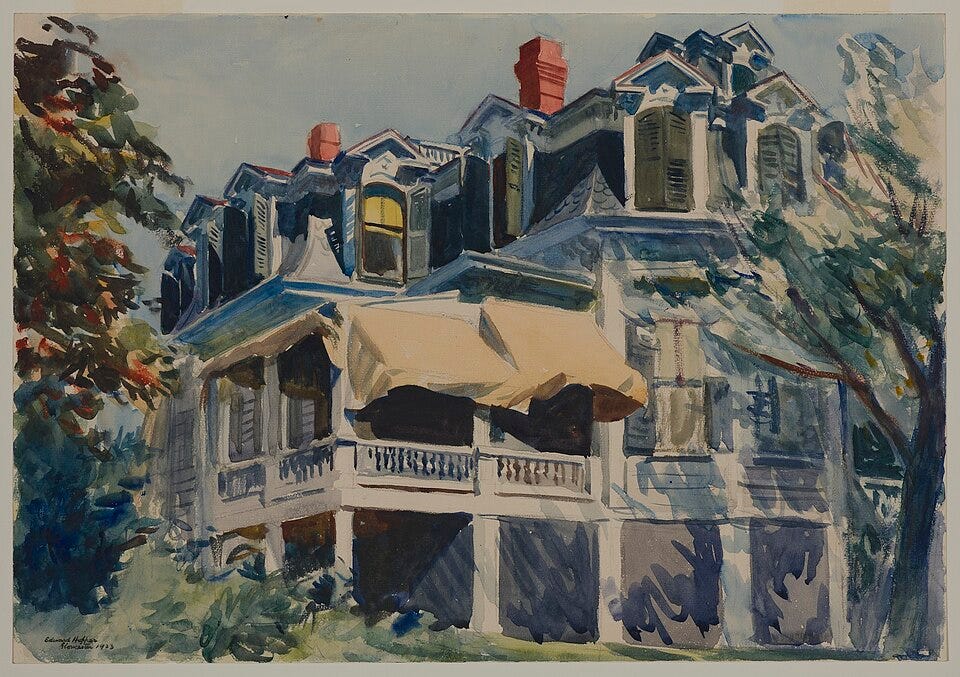

The real turning point in Hopper’s career came in 1923. Josephine Nivison, a fellow painter who had studied alongside him under Henri, helped get his Gloucester watercolors into a Brooklyn Museum show. The museum ended up purchasing The Mansard Roof. Then in 1924, his watercolor show at the Rehn Gallery sold out completely. After decades of frustration and commercial failure, Hopper could finally quit illustration work and paint full time.

But 1924 brought another major transformation. On July 9 of that year, Hopper married Jo.

She was everything he wasn’t. Vivacious, talkative, socially engaged, ambitious for her own artistic career. Their courtship was brief and their marriage was immediate. What followed would shape not just Hopper’s personal life but the development of his artistic vision in ways that are impossible to fully untangle.

Jo became his business manager and record keeper, his essential partner in all the practical matters of artistic life. She kept meticulous ledgers of every painting he made. The date, the location, the price, detailed descriptions of each work. These documents are extraordinary when you look at them now. They’re a careful documentation of a career that depended entirely on her administrative labor, her organizational genius, her willingness to manage all the aspects of professional life that Hopper found overwhelming.

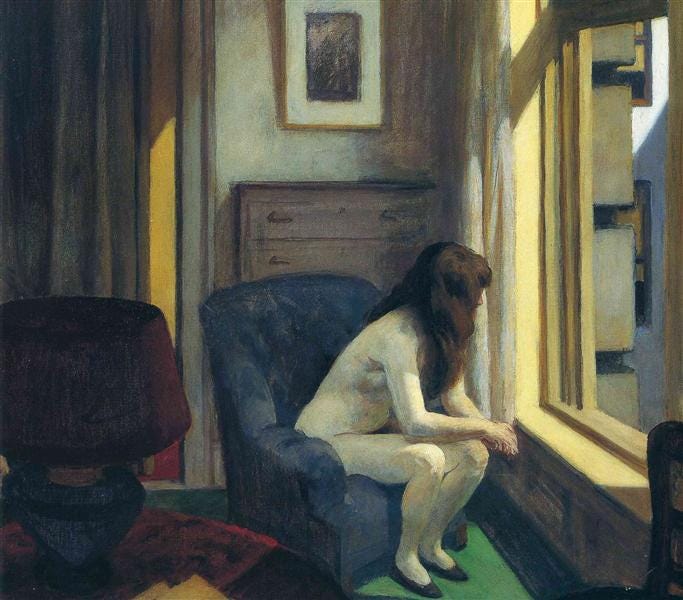

But Jo also became something else. She became his principal model. By most accounts, Jo insisted on this arrangement, often to the exclusion of other women. Multiple sources describe her jealousy as fierce, almost pathological. And Hopper accepted it. For the next forty-four years, until his death in 1968, Jo’s body and features would supply the template for many, perhaps most, of the women in his paintings.

This arrangement would have profound implications for Hopper’s work. It didn’t create his vision from scratch. That sensibility was already there, already formed. But it shaped how that vision could be expressed. It limited his observational range while simultaneously forcing a kind of psychological intensity that might not have emerged otherwise. It’s one of those situations where constraint and creativity became so intertwined that you can’t separate them cleanly.

Reclining Nude (1924) is one of the first paintings under this new arrangement. It’s Jo’s body, rendered with formal precision—light and shadow, form and space. Already you can see Hopper beginning to develop the visual vocabulary he’ll work within for the rest of his life. The painting is accomplished, technically masterful, but it raises a question that will haunt his entire career: What else might he have painted?

Here’s where we need to understand something crucial about artistic constraint: if Hopper had access to a wider range of models—different ages, body types, expressions, emotional tones—he might have explored more variety in human connection, warmth, sensuality, social context. His work might have opened outward, encompassed more of human experience.

Instead, we get:

One woman (primarily)

Posed over decades

Often in solitude

Often in passive states

Often stripped emotionally, physically, or both

Jo’s limitation forced Hopper to paint what wasn’t said, what wasn’t shared, what couldn’t be expressed. So his paintings tighten, emotionally and formally. They become compressed theaters of silence, tension, and unexpressed desire. If Hopper had been allowed more muses, we might have gotten more dialogue, more variety, more openness. But because of Jo, we got stillness. We got psychological lockdown. We got boundaries.

And paradoxically, this became his genius.

One of Hopper’s most important early works came in 1925 with House by the Railroad. This wasn’t an idealized farmhouse or a nostalgic tribute to rural life. It was stark, cropped, eerily silent. There are no people in it. No cars. Just a brooding Victorian house sitting beside railroad tracks, cut off from the world by progress itself. The painting would go on to inspire everything from Hitchcock’s Psycho to decades of suburban disillusionment in American cinema.